The Canadian Electrical Code in some instances limits maximum applied voltages to protect the general public and inexperienced people from electrical shock hazards. Unqualified persons are at greater risk due to their inability to identify electrical hazards and understand electrical shock risks. This article reviews some of the circumstances where the code prescribes maximum voltages to minimize exposure to serious electrical shock.

The first and most obvious voltage restriction is in our home. Rule 2-106 prescribes 150 volts-to-ground as the maximum voltage in dwelling units. A dwelling unit is where we live, such as a single family home, townhouse or apartment. It follows that this rule limits the supply voltages to dwelling units to either 120/240 volts single-phase or 120/208 volts three-phase. As much as possible, the intent is to protect occupants and other persons considered unqualified against undue electrical shock risks.

However, multi-family residential buildings often employ qualified and experienced maintenance staff. When so, Rule 2-106 does permit some exceptions for multi-family buildings where the electrical load exceeds 250 kVA and if such maintenance staff is on hand. Here up to 347/600 volts may be supplied to permanently installed:

- Space heating controlled by low voltage wall thermostats

- Water heating

- Air conditioning

Rule 2-106 is relaxed for such applications only when assurance is given that management will employ qualified people, capable of recognizing and dealing with the personal risks when maintaining this equipment.

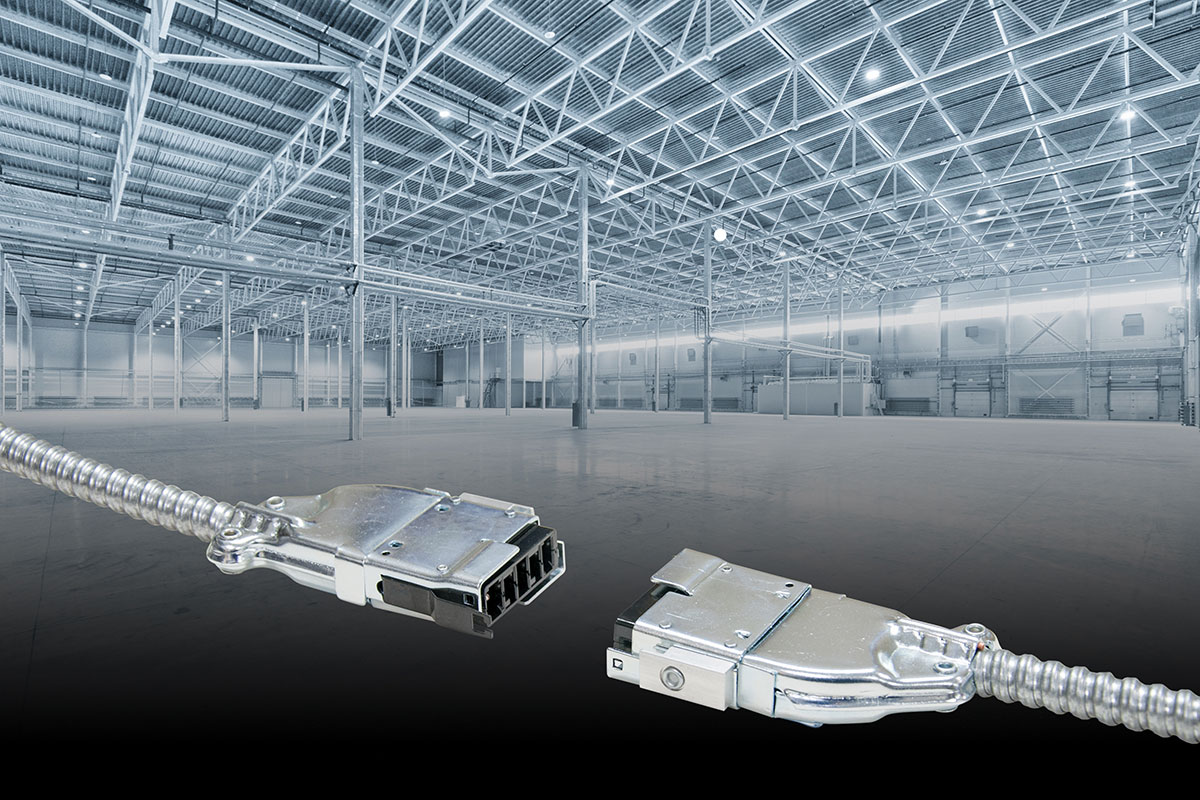

Similarly, Rule 30-102 further supports Rule 2-106 by requiring that lighting circuit voltages in dwellings be limited to either 120/240 volts or 120/208 volts. But for other than dwellings, Rule 30-102 allows up to 347/600 volts. Other than dwellings includes industrial or commercial lighting, but also lighting in common areas of apartment buildings or other multi-family buildings such as hallways, basements and parking lot lighting. Here again, it is expected that this equipment would be maintained only by qualified people.

A similar shock issue applies to ballast type lighting, which depending on its design, may produce high open circuit voltages. Rule 30-706 addresses this safety issue. Some ballast type lighting, in particular instant start fluorescent lighting produces extremely high open circuit voltages. High starting voltage allows the lamps to light quickly without cathode heating or other means to assist starting.

And to further limit shock risks, Rule 30-706 prohibits fluorescent fixtures having open circuit voltages above 300 volts from use inside dwellings unless the live parts are enclosed to prevent inadvertent contact during lamping or relamping, and Rule 30-802 prohibits outright the use of any lighting fixtures having open circuit voltages more that 1000 volts within dwellings.

Neon tubes operate at even higher voltages and they can be very dangerous if incorrectly installed, maintained and when unqualified people may come in contact with them. To reduce such risks, Rule 34-300 restricts maximum open circuit voltages for neon signs and outline lighting to a maximum of 15,000 volts and 7500 volts phase to ground if neon tube circuits are provided with secondary ground-fault protection. If not, open circuit voltages must be limited to:

- 6000 volts for transformers that have isolated secondary windings (not autotransformer types)

- Equipment that has factory-installed (no interconnecting field wiring) between the transformers and the neon tubing.

The reason for the above voltage restrictions is to limit exposure to electrical shock to a general public that is usually unaware of the risks.

Dry niche type underwater lighting fixtures are installed in the walls of swimming pools behind a glass lens, sealed to exclude water. It is well recognized that people in or around swimming pools are vulnerable to electrical shocks due to the presence of moisture and low body resistance to current flow. It’s particularly important to prevent stray currents in the water, normally achieved with correct grounding and bonding methods. But to further limit electrical shock risks, Rule 68-066(3) also limits both the lighting circuit supply voltage and lighting ballast open circuit voltage to maximum 300 volts during both starting and operation.

The code also limits electrical shock hazards in outdoor electrical substations supplied at more than 7500 volts in the event of a system ground fault. Currents may flow through the earth and away from the fault location, thereby creating ground potential rise on station grounding systems and on all metallic objects such as electrical equipment and structures in the station.

A person who happens to be inside a high voltage substation during a ground fault is at risk from electrical shock. Rule 36-304(2) and Table 52 helps reduce this risk by limiting step and touch potentials to “tolerable” levels. For example, during a one second ground fault in an outdoor station with a crushed stone surface, Table 52 specifies maximum step and touch voltages of 2216 volts and 626 volts. You will recall that step voltage is voltage between your feet and touch voltage is voltage between an energized object and your feet during a ground fault. The 150 mm crushed stone surface of the station further reduces the shock hazards.

As in the case of previous articles, you should consult the electrical inspection authority in each province or territory for a more precise interpretation of any of the above.

Find Us on Socials