As buildings age, their electrical systems age with them. Renovating those older systems adds flexibility through modern wiring practice and increases safety. However, the electrical contractor and the authority having jurisdiction need to agree on the ground rules that will apply to the construction. This article has two purposes. First, it looks at some general principles of responsibility for National Electrical Code compliance in renovation projects, and then it takes a practical look at construction issues that often result in NEC application controversies during renovations. The NEC is not, by its own terms, retroactive. The extent to which it will be applied to an existing condition is left to the enforcing jurisdiction. Space does not allow this article to cover when existing defects must be corrected simply because the wiring has deteriorated, and not because a renovation contract has triggered an electrical permit and subsequent inspection. This is a separate topic involving other standards, such as NFPA 73, Electrical Inspection Code for Existing Dwellings.

Some Ground Rules

A word of caution is in order here. Do not view the principles that follow as legally binding or comprehensive, because enforcing jurisdictions can and probably will differ on the details. Instead, look at this discussion as a starting point for considering the types of issues to sort out between the inspector and contractor, preferably before the contractor has made a binding agreement with the owner as to the price and scope of work.

If regulations addressing these issues are not set out in writing ahead of time, the author strongly recommends enforcing agencies consider engaging in an appropriate rule-making procedure (hearings, formal vote by regulatory authority, and subsequent publication) to do so. The financial consequences for a contractor or for an owner can be substantial. If those consequences have the appearance of being arbitrary or capricious, or simply serving the special interest of the electrical trade, the potential legal and political ramifications may inadvertently destroy the technical independence of the inspection authority. Everyone loses from such an outcome.

Will rules for new buildings apply? There may be a threshold, such as a percentage of the building involved or a change of use category as covered in the applicable building code, beyond which the work is considered new construction. If this is the case, all wiring must meet the current NEC requirements that would apply in the same jurisdiction to new buildings.

Violations in other areas. If the work qualifies as a renovation, then areas of the building unaffected by the renovation may be exempt from compliance with current NEC provisions. For example, if the electrical permit application covers a living room and den, few if any jurisdictions would attempt to legally compel the provision of GFCI protection for unprotected bathroom receptacles elsewhere in the occupancy.

The actual work. The renovation work itself must usually comply with all applicable current NEC requirements. If the contractor (or inspector) believes otherwise, such as when a contractor seeks permission under 90.4 for an alternate procedure believed to offer equivalent safety, then the issue must be fully explored as soon as possible. Note that the equivalent safety provisions of 90.4 now are allowed only by special permission. This means that the inspectional authority will have to make a formal, written finding of equivalence, for which it may be held accountable subsequently. Such allowances require careful consideration.

Violations created by renovations. The renovation work usually will not be allowed to create a violation of the NEC in a supposedly unaffected portion of a building. For example, suppose a dining room and kitchen renovation changes the location of a doorway into the adjoining living room such that the receptacle placements in that room no longer comply with 210.52(A). The contractor and inspector would be well advised to discuss whether the receptacle outlets in the living room must be added or relocated accordingly.

Existing violations in renovated areas. There may be jurisdictional limits on whether an existing violation in the renovated area must be corrected. Some jurisdictions normally insist on this, and others do not. Some ask for corrections only if the renovation makes the existing problem worse. This topic must be fully explored between the inspector and the contractor ahead of time for two reasons. Considerable judgment may be required on the part of the inspector, and that judgment may have enormous financial implications. For example, 230.70(A)(2) now excludes service disconnecting means from bathrooms, but that rule is relatively recent. Many bathrooms, especially in nonresidential occupancies, contain existing service equipment. If such a bathroom were being reconstructed, the cost of relocating the service would probably dwarf the cost of all remaining electrical work.

Existing hazards.Most jurisdictions have a mechanism for compelling the correction of existing code violations that create a clear and present danger. If this is the case, the contractor needs to know whether this work must be included in the renovation, and upon whom the financial responsibility for corrections will fall.

Renovation Code Issues

Although some of the following issues frequently arise in new work, they come up so often in renovations that they deserve special consideration here.

Shallow boxes.At one time the NEC made distinctions between old and new work regarding the minimum allowable depth of a box, but no longer. Boxes must have a minimum depth of 1/2 in. Photo 1 shows a 6-cu-in., 4-inch-diameter ceiling pan without cable clamps. This is the smallest box permitted for Type NM cable because a single 14-2 cable, with its separate equipment grounding conductor, accounts for all of the volume1 [review 314.16(B)]. These boxes are very important in renovation work, because they often avoid the necessity of removing a ceiling (or wall) finish.

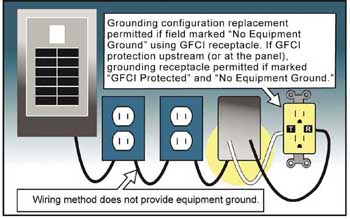

Figure 1

Receptacle replacements.Most renovations involve receptacle replacements. In general, receptacles [per 406.3(D)(1)] must have a grounding configuration, and the grounding terminal must actually be connected to the circuit equipment grounding conductor. Figure 1 shows a replacement receptacle on a circuit that has no equipment grounding conductor. In this case, the receptacle could be replaced with a nongrounding configuration, or a grounding configuration could be used if GFCI protection is arranged for the outlet.

In general, receptacle configurations advertise circuit characteristics, and users are entitled [per 406.3(A)] to believe that the configuration is truthful. What about 406.3(D)(b) and (c) where we end up with a grounding configuration without an equipment grounding connection? The NEC balances the enhanced shock protection rendered by the GFCI protective device with the absent grounding connection in such cases through the use of additional marking. A GFCI receptacle, which inherently advertises its function, must be marked “No Equipment Ground” and if the protection is upstream the marking must also include the phrase “GFCI Protected.”

Photo 1. A 6-cu-in., 4-inch-diameter ceiling pan without cable clamps.

The current NEC requires GFCI protection for many receptacle outlets, including those (125-volt, 15- and 20-ampere) in kitchens generally. It also requires [per 406.3(D)(2)] GFCI protection for all receptacle outlets where a receptacle is replaced in a location where the current NEC requires such protection. This is an interesting case from a regulatory standpoint because it may appear to violate the principle that the NEC is not a retroactive document. However, this requirement only applies when an installer performs an action at the outlet, that of replacing a receptacle. No NEC rule requires an existing receptacle to be disturbed, and therefore issues of retroactivity remain with the local jurisdiction.

Photo 2. This is because indoor wet locations frequently involve applications where a “bubble” cover of the sort shown in photo 2 is not rated for upward-directed hose streams, and the only possible solution is a screw-on gasketed cover.

Outdoor receptacles.Renovations do not just involve interior alterations. Frequently receptacles are added for use outdoors. The NEC now requires all 15- and 20-ampere receptacles (125- and 250-volt) located outdoors to have covers that are weatherproof even if the receptacle is in use. This is a major change from the 1999 NEC, which only required such covers if the use would continue on an unattended basis. Note that this requirement does not apply, however, to indoor wet locations. This is because indoor wet locations frequently involve applications where a “bubble” cover of the sort shown in photo 2 is not rated for upward-directed hose streams, and the only possible solution is a screw-on gasketed cover. The NEC, so far, is silent with respect to protecting such receptacles located indoors.

Annular space around box openings.Renovations always involve partition openings, and the author has found that with good communication, 314.21 can be used by the inspection community to make life easier for electricians. These openings must be repaired so there is no gap greater than 1/8 in. at the edge of the box. The dimension comes from the measurement UL uses as the maximum gap that can be left in order to retain the fire-resistance classification of the box (see 300.21). Although many electricians think this makes them plasterers, in fact the problem is frequently poor-quality drywall installation.

If the inspection community makes it known that this rule will be enforced, electrical contractors can offer the general contractors a choice: police their drywall subcontractors, or pay electrician’s rates for drywall repairs. The author has seen the quality of drywall installations improve dramatically in jurisdictions where this has been tried. Remember that when the drywall fits close to the box, the plaster ears on the device will seat securely to the drywall. This avoids the labor required to apply spacers under the yoke in order for it to be “held rigidly at the surface of the wall” [per 406.4(A)].

Boxes in combustible material.Renovations often involve changing wall finishes, such as adding paneling over existing drywall. Boxes must not be recessed in combustible walls (per 314.20), and this means bringing the box forward. If that is not practicable, rings such as the one shown in photo 3 can be used. Although most electricians are aware of this rule, it has a frequently misunderstood companion. NEC 314.25(B) and 410.13 require that when luminaires are installed on combustible surfaces, the surface behind the canopy is to be covered with noncombustible material. This covering need not be metallic; the fiberglass batting often packed in luminaire canopies can serve the function. Be sure the installer has routed the fixture wires behind the fiberglass and out near the center of the canopy. That way they will not rest against the combustible surface, defeating the purpose of the rule.

Photo 3. Renovations often involve changing wall finishes, such as adding paneling over existing drywall. Boxes must not be recessed in combustible walls (per 314.20), and this means bringing the box forward. If that is not practicable, rings such as the

Ceiling-suspended (paddle) fans.Paddle fans are popular and the ones with lighting fixtures attached below them frequently substitute for traditional overhead lights. Safely supporting paddle fans has been a major issue in the industry. Traditional boxes and their product standards have generally assumed a static load held in a particular direction. Paddle fans, especially when rotating fast and with some blade imbalance, impose a load that traditional boxes were not designed to support. In addition to causing box support failures, paddle fan loading overstresses conventional box support methods. In fact, most fan support failures probably have more to do with inadequacies in the way the box was secured to framing than with the integrity of the box itself. Although this is time consuming, inspectors should periodically review fan-box installations for the use of robust support hardware and strict compliance [per 110.3(B)] with the manufacturer’s mounting instructions.

The NEC recognizes boxes specifically listed for the support of paddle fans (see photo 4). They can generally support 35-lb fans, and heavier ones if so listed. They undergo a rigorous testing protocol involving a very heavy fan run for a long period at very high speeds with a severe blade imbalance, and with one of the screws that secure the fan to the box deliberately loosened in some cases. Contractors should discuss this carefully with their customers, because it is much easier to rough in paddle fan support boxes at the likely locations than it is to install them at existing outlets later, especially if there isn’t framing in place that would allow independent fan support at the outlet location.

Photo 4. The NEC recognizes boxes specifically listed for the support of paddle fans

With respect to framing support, the NEC allows paddle fans of any weight to be supported directly from structural elements of the building even at a traditional outlet box, because the building structure and not the box will be the primary support of the fan. This procedure has the additional virtue of allowing a fan to be mounted on any size or configuration of boxes, extension boxes, and plaster rings, some or all of which may not be available in a form listed for direct fan support.2

Connections to concealed knob-and-tube wiring. In cases where the existing wiring is concealed knob-and-tube, the NEC does allow it to be extended from an existing application. But that is seldom practical because the hardware is no longer readily available, and the existing knobs salvaged from old jobs have internal spacings for old Type R conductor insulation that will not work on today’s thinner insulated conductors. Concealed knob-and-tube, as a wiring method, has no equipment grounding conductor carried with it. Over the generations, NEC provisions have changed to the point that it is almost impossible legally to wire anything without grounding it. For example, until the 1984 NEC, what is now 314.4 only required the grounding of metal boxes used with concealed knob-and-tube wiring if in contact with metal lath or metallic surfaces. Now all metal boxes must be grounded without exception.

Meanwhile, grounding has been getting more difficult to arrange to remote extensions of concealed knob-and-tube outlets. Until the 1993 NEC, you could go to a local bonded water pipe to pick up an equipment grounding connection, and then extend from there with modern wiring methods. Now 250.130(C), which governs this work, requires that the equipment grounding connection be made on the equipment grounding terminal bar of the supply panelboard, or directly to the grounding electrode system or grounding electrode conductor. You will not be inspecting grounding connections associated with concealed knob-and-tube wiring in a steel-frame building. Rather you will see this in old wood-frame buildings, probably residential. In such occupancies, even if the water supply lateral is metallic, the water piping system ceases to be considered as an electrode beyond 5 feet from the point of entry. This usually means fishing into the basement. If the contractor can fish a ground wire down to this point, he or she can fish a modern circuit up in the reverse direction and avoid the entire problem.

It is true that some geographical areas have more extensive use of slab-on-grade construction, and here interior water piping is sometimes permitted to qualify as electrodes because the pipes extend to grade for the minimum threshold distance of 10 feet, and thereby allow interior connections. But in almost every case, extensions of concealed knob-and-tube wiring do not do well upon close inspection.

In addition to the grounding issue, beginning with the 1987 NEC this wiring method cannot be used in wall or ceiling cavities that have “loose, filled, or foamed-in-place insulating material that envelops the conductors.” This effectively means that such cavities cannot be insulated, because the only method of compliance involves opening all the walls to install board insulation products, and no contractor is going to keep this wiring method with the walls open. This rule is particularly controversial because, to the extent enforced in existing construction, it is a powerful economic disincentive for owners to retrofit thermal insulation.3

Communication: Making the Process Work

Renovations offer a unique opportunity to bring parts of a building into compliance with current code requirements, increasing safety. However, if the requirements are too onerous, the owner may decide to forego the effort. The inspection community has the delicate responsibility of weighing how to apply the principles at the beginning of this article to the various code issues involved, such as those addressed in the second half of the article.

How well we succeed in making this process work will usually turn on how well we communicate among ourselves and with the owners and other stakeholders. The contractor has to take the time to be clear with the owner as to code issues in the owner’s design preferences. The contractor also needs to build into this discussion an awareness of what issues need to be interpreted by the inspector, and to then provide plans for the inspector on a timely basis. The inspector needs to set aside enough time to review the plans so the contractor and owner are not surprised after they have settled on a contract. If that time is not available, and with today’s economic trends that is too often the case, there should at least be a detailed telephone conversation. In addition, both contractors and inspectors need to be involved with organizations like IAEI, through which collective efforts, such as the Inspection Initiative, can be focused on the political authorities who often make the final decisions based on fees and staffing levels.

1Herbert P. Richter and Frederic P. Hartwell,Practical Electrical Wiring, 18th ed., Park Publishing, Minneapolis, Minn., 2001, p. 394

2Ibid, pp. 356-357

3Ibid, pp. 392-393

The information in this article is excerpted fromPractical Electrical Wiring, 18th edition, and Wiring Simplified, 40th edition. These books may be purchased from IAEI — 800-786-4234.

Find Us on Socials