The National Electrical Code (NEC) has undergone significant changes over the decades, particularly in how it defines and regulates electrical services. The journey from early editions of the NEC to the modern 2023 code is a fascinating look at how electrical safety, technology, and industry practices have evolved. Let’s take a deep dive into the history of service definitions and how the industry has shifted its understanding of what constitutes a service. The next chapter of this journey very well could be about to unfold; we will pose some questions that just may spark your thinking.

1923, A Simpler Era

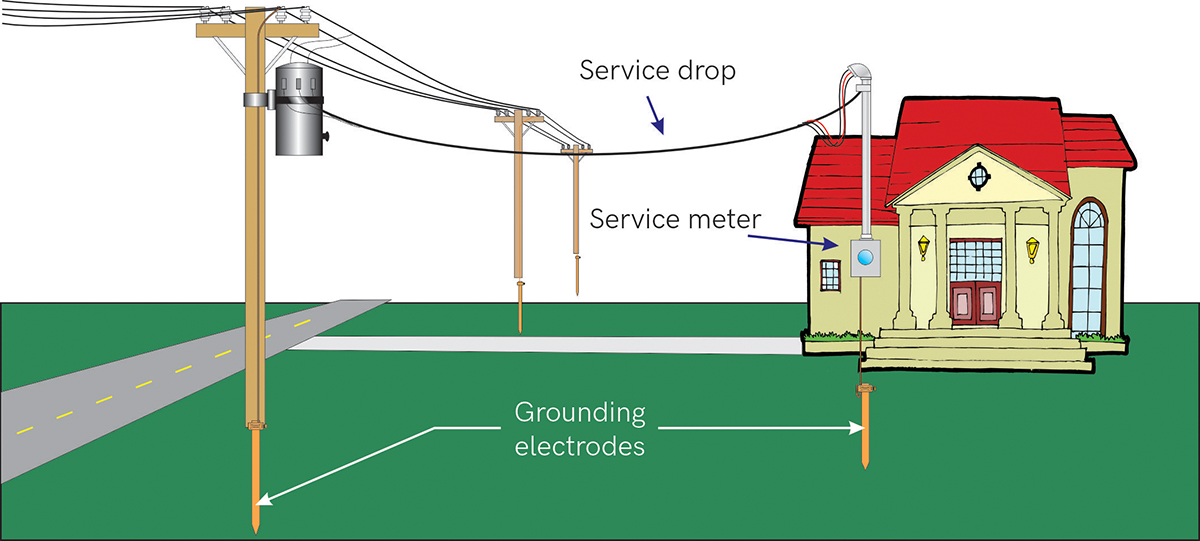

In the 1923 edition of the Code, the definition of “service” was quite simple: “That portion of the supply conductors which extends from the street main to the service switch of the building supplied.” Notably, the term “utility” was absent from the definition. At the time, it was implicitly understood that power came from a utility, but there was no explicit mention of the term “utility”.

NEC 1923 also contained a list of installation rules covering generators, motors, switchboards, and grounding but had no references to modern innovations like photovoltaic systems, energy storage, or electric vehicle charging equipment. The industry was primarily concerned with distributing power from the street mains to buildings.

In 1923, homes were hubs of tradition and transformation amidst early technological advances. Many still relied on gas, wood, or coal for heating and cooking, with electric lighting gradually replacing gas lamps. Central heating and air conditioning were absent, and ventilation through windows prevailed. Kitchen tools were manual, and iceboxes kept food cool before refrigerators became common. No debates on receptacles for islands or peninsulas occurred during this time for sure. Radios and telephones were emerging, while indoor plumbing and basic electrical appliances were slowly becoming more widespread. Despite safety standards and technology not yet reaching modern levels, the 1923 home marked a pivotal transition toward today’s comforts and innovations.

The 1940s: A Shift in Terminology

By 1940, the code expanded the definition of “service” to include not just conductors but also equipment, marking a shift in understanding. The 1940 definition read: “A service is the conductors and equipment for delivering electric energy from the secondary distribution or street main, or from a distribution feeder, or from the transformer to the wiring system of the premises served.”

This new wording introduced a directional flow of current and recognized different types of power distribution beyond a simple street main connection. However, the term “utility” was still not explicitly mentioned. The industry recognized the terms “secondary distribution,” “distribution feeder,” and transformer as those being supplied to connect a utility. Without context, one could use the terms “distribution feeder” or “transformer” to be any part of the power distribution system and not just related to a utility. The mindset of the time plays an important role and demonstrates how our minds fill in the gaps when the words don’t quite hit their mark.

By the 1940s, American homes had become increasingly electrified, especially in urban areas, where incandescent lighting was standard, and Art Deco-style fixtures reflected modern design. Rural homes, however, often still relied on gas lamps. Electrical appliances like refrigerators, electric stoves, and washing machines were becoming more common, though many households still used manual tools. Radios were household staples, and telephones were spreading, with rotary dial models gaining popularity. Electrical safety was improving, but outdated wiring remained a concern, as fire alarms and smoke detectors were not yet widespread. This decade marked a transition toward greater convenience, setting the stage for the fully modern home.

1947-1990: Simplification and Standardization

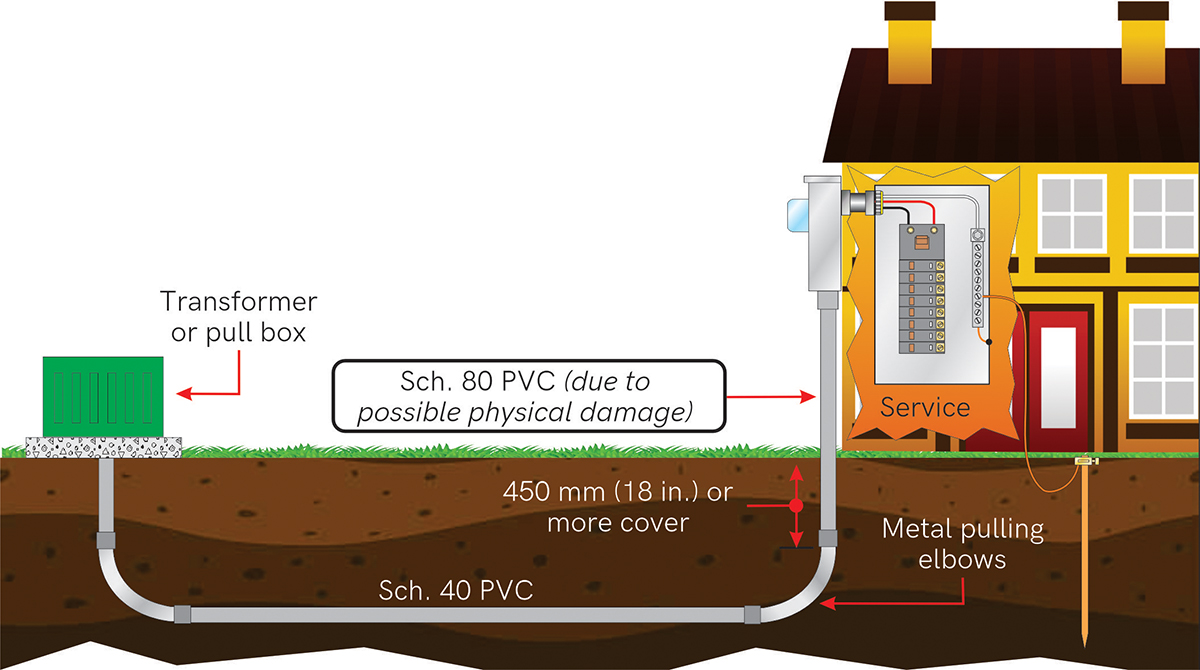

In 1947, the NEC streamlined the service definition to: “The conductors and equipment for delivering energy from the electricity supply system to the wiring system of the premises served.” This version persisted through the 1990 edition and introduced a more generalized term, “electricity supply system,” which still avoided the word “utility” and was not a defined term itself.

During these decades, additional service-related terms were introduced, such as service entrance conductors, service equipment, and service raceways. These refinements helped better define different components of a service installation but still did not formally distinguish between utility and non-utility power sources. For many of these years, if not for all of them, alternative energy systems were not the norm for commercial and residential applications. One could argue that industrial applications have historically included other sources like batteries but not the alternative energy solutions that we know and love today. Our minds are still left to fill the gaps that the words did not deliver.

By 1990, American homes were fully electrified, with incandescent and fluorescent lighting common, while energy-efficient compact fluorescent bulbs (CFLs) began appearing. Central heating and air conditioning, powered by electric heat pumps or gas furnaces, became standard, replacing older heating methods. Kitchens featured electric stoves, microwaves, refrigerators with built-in ice makers, and dishwashers, making daily tasks more convenient. Home entertainment advanced with large-screen TVs, VCRs, and the rise of personal computers with dial-up internet. Cordless phones became widespread, and home security systems with motion detectors and alarms gained popularity. Smoke and carbon monoxide detectors improved safety, marking a shift toward more efficient and technologically integrated homes.

1953: Utility Concept Becomes Clearer

Before we continue beyond 1990, we must pause for a review of some key changes that occurred as part of NEC 1953. During this cycle, the purpose and scope sections began addressing the role of utilities more explicitly. The 1953 edition included language specifying that the NEC did not cover “installations in mines, ships, railway cars, automotive equipment, or the installations of equipment employed by a railway, electric, or communication utility in the exercise of its function as a utility.” This clarification, in the opinion of this author, signaled the beginning of clearer distinctions between what was and was not governed with those systems under utility control out of reach.

By 1956, the NEC had refined this language even further, reinforcing that utility-owned systems fell outside its scope. However, the defined terms within the NEC on which this article is focused still did not include the word “utility” explicitly until much later. I will argue that the changes in 1953 helped fuel the fire in this regard.

1993: The Introduction of the Service Point

One of the most significant changes occurred in the 1993 code with the introduction of the term “service point.” Service point was defined as “the point of connection between the facilities of the serving utility and the premises wiring,” This change marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of the code, as it formally recognized the utility’s role in the electricity supply chain.

The addition of “service point” created a ripple effect across multiple NEC sections, leading to revisions in the defined term premises wiring system and service conductor regulations. However, this also introduced conflicts between the previous language and the new service point concept, particularly in Article 230, which required further refinements in subsequent editions. When changes occur in the NEC, the public begins the review process through debates at IAEI meetings that help shape this industry resource.

Previously, the term “service” had focused more on the physical conductors and equipment. With the addition of the term “service point,” the NEC now introduced the concept of a clear delineation between the utility’s infrastructure and the premises wiring. This allowed for better clarity on the responsibilities of both the utility and the consumer.

However, this change also introduced confusion regarding the classification of certain power sources. In particular, alternative energy systems, such as photovoltaic (PV) systems and generators, posed new challenges for code interpretation as their connections to the service point began to blur the lines between utility and non-utility sources.

1996-1999: Resolving Service Conductor Conflicts

Just three years later, in fact the next code cycle for NEC 1996, a change to the definition of service conductors left the definition as “The conductors from the service point or other source of power to the service disconnecting means.” This change did not add clarity but rather, in my opinion, introduced ambiguity, as “other source of power” could be interpreted to include generators and photovoltaic systems. With ambiguity comes confusion and when trying to apply requirements ambiguity presents challenges for everyone. IAEI meetings across the country probably debated this at nauseum. So much so that by 1999, the NEC removed the phrase “other source of power” and revised the definition of service conductors to “The conductors from the service point to the service disconnecting means.” At the same time, the definition of service was changed to explicitly state: “The conductors and equipment for delivering electric energy from the serving utility to the wiring system of the premises served.”

For the first time, the word “utility” was officially part of the NEC definition of “service.” With this move, any lingering ambiguity about what constituted a service was eliminated. Or was it?

2020: Introduction of Power Source Output Circuit

The 2020 edition of the code introduced another important shift. As renewable energy systems, such as solar panels, became more widespread, the NEC faced the challenge of defining how power from these sources should be treated within the framework of “service.”

One notable change was the introduction of the term power source output circuit to describe conductors connecting distributed generation sources (e.g., photovoltaic systems) to electrical distribution equipment. This defined term was placed in Article 705, “Interconnected Electric Power Production Sources,” as part of 705.2, Definitions, and so only applied to the requirements found in Article 705. The term was defined as “The conductors between power production equipment and the service or distribution equipment.” This addition sparked debates because of the overlap between this defined term and the defined term “Service Conductors.” The overlap occurs with the inclusion of “and the service.” The debates focused on those conductors that connect power production sources to the service, questioning whether those are service conductors or power source output conductors, both of which are defined terms and have different installation requirements.

We must remember the fact that the defined terms found in Article 100 or the nnn.2 sections of each Article are the gateways to requirements found in the code. Once we identify what we are addressing, whether it be a room, i.e., kitchen, or a component, i.e., service conductor, then we go elsewhere to determine the installation requirements pertaining to that which we just defined. When reviewing the conductors from a power source like a generator or inverter to service entrance conductors, we need to understand what they are. For NEC 2020, two terms could apply to these conductors. One is the term “Service conductor,” which is defined in Article 100 as “The conductors from the service point to the service disconnecting means.” The other is the term “Power Source Output Circuit,” which is defined in 705.2 as “The conductors between power production equipment and the service or distribution equipment.” A decision has to be made to either go to Section 705.11, Supply-Side Source Connection, or Section 705.30, Overcurrent Protection, or even into Article 230 for the installation requirements for these conductors.

The introduction of this term spurred many debates at IAEI meetings across the country. These debates drove the creation of a correlating committee task group to work through the ambiguity and bring clarity to the requirements.

2023: Clarifications for Alternative Energy Sources

Task group work during the 2023 code cycle to review and address the discrepancies in terminology produced some important public inputs and comments. The task group consisted of individuals from Code Making Panel 4 (CMP 4), which focused on alternative energy solutions, CMP 10 for overcurrent protection, CMP 5 for grounding and bonding expertise, and finally CMP 9 for transformer applications. The result of this effort brought forth an NEC 2023 code with additional clarifications.

One of the important aspects of clarity brought to the document was that the conductors connected on the line side of the service disconnecting means are considered service conductors and the disconnect on which those conductors land is a service disconnect. The requirements found in Article 705, specifically Section 705.11 titled “Source Connections to a Service,” were modified to add this clarification. Section 705.11(B), Conductors, identify these conductors, the ones that connect the power production equipment to the service, as service conductors. The clarity seems to be there, but one could argue that if you pop up 30,000 ft and review other terminology and requirements, the waters are still muddy.

If you recall, the stimulus for debates was in the term power source output circuit as it included the word service which was problematic. The term power source output circuit was replaced in NEC 2023 with the term power source output conductors and moved to Article 100, expanding its application as a generally defined term used throughout the code. This term, power source output conductors, is defined as “The conductors between power production equipment and the service or other premises wiring.” Including the term “service” in this definition is still problematic. Section 705.11 calls these conductors service conductors with the installation requirements for them found in Article 230, but if you call these same conductors power source output conductors, then you follow the requirements in 705.25. There are differences in installation requirements and this correlation issue can drive confusion.

Yet another opportunity for clarity was missed during the 2023 Code cycle in the term power production equipment. This term is defined as “Electrical generating equipment supplied by any source other than a utility service, up to the source system disconnecting means.” This definition says that electrical generating equipment is supplied by a source. Electrical generating equipment, in my opinion, is a source.

Just when you thought clarity existed, we see that the conductors between the power production equipment and service are referred to as both a service conductor and a power source output conductor, both of which have specific requirements found in two different areas of the code with different installation requirements.

Clarity is critical, especially today. Homes today are much different than what they were in the 1920s. They are defined by advanced electrical systems, with smart lighting controlled by voice commands, motion sensors, or mobile apps, alongside energy-efficient LED bulbs. Smart thermostats optimize heating and cooling, integrating with electric heat pumps and solar-powered systems for efficiency. Kitchens feature smart refrigerators, induction stoves, and voice-activated appliances, while bathrooms include smart mirrors and high-tech toilets. Home automation connects lighting, security, and entertainment through centralized hubs, with video doorbells, smart locks, and security cameras enhancing safety. Sustainability is prioritized with solar panels, energy-efficient appliances, and eco-friendly materials, making today’s homes both technologically advanced and environmentally conscious.

Conclusion: The Journey of the Service Continues

Reviewing the evolution of service definitions in the NEC offers valuable insights into the development of electrical safety and industry practices. From the simple wording of 1923 to the detailed definitions of today, the NEC has continuously refined its approach, seeking clarity and safety in electrical installations. It is a fact that our power distribution system installations have changed considerably over time and our terminology has been trying to keep up. In my opinion, we have not reached clarity for service applications. This journey is not over. Some even question the tie between service and utility, stating that a service should not be aligned with the utility at all. Comparisons could be drawn and demonstrate that there are no differences between service circuit diagrams and many other areas of the power system other than who you need to call to establish an electrically safe work condition. Does that little electron know it’s coming from a utility or a local generator? Is it really that smart? The hazards are the same and should be treated the same. This is food for thought for the next chapter in the history of the service. I am looking forward to the IAEI Analysis of Changes for the 2026 edition of the National Electrical Code to see what the next chapter in the electrical service has to offer.

Find Us on Socials