Harnessing electricity for a variety of uses helped usher in the great industrial and societal advances of the late 19th century. Arguably, the household use of electricity is one of the greatest advancements in modern living. It powers household appliances in the kitchen, laundry, and elsewhere. It lights our homes after dark and educates and entertains us with computers, gaming consoles, sound systems, and televisions. In short, it brings our homes to life.

Most of the time, it’s easy for the majority of us to take the power of electricity for granted. In most instances, it’s clean and safe. That is as long as it stays in a controlled circuit. Electricity that strays can be dangerous and deadly. This can be especially true at the scene of fires.

When responding to emergencies, including structure fires in one- and two-family housing units, safety is always at the top of the list of firefighter priorities. Fire officers serving as incident commanders routinely identify and secure utilities, including gas, electricity, and water, to minimize hazards to firefighters working to rescue people and extinguish fires in homes.

Locating and shutting off the electric service to a structure is typically done very early in a fire event. Doing so helps reduce the risk of firefighters encountering stray currents and being electrocuted. In most cases, firefighters are able to quickly find a master circuit breaker and isolate power supplies even before the arrival of a service technician from the utility company.

Incident commanders usually try to do this as soon as reasonably possible and often assign a fire crew to locate the main circuit breaker panelboard. This, in turn, allows them to shut off the main circuit breaker to isolate power to circuits extending away from the main panelboard.

Most firefighters are taught that we need to isolate power by using the main breaker and to not disturb individual circuits. This is done to help protect evidence at fire scenes until investigators can arrive on the scene and conduct initial origin and cause determination. Prior to 2020, the master circuit breaker box could often be found in the garage or basement of individual houses and duplexes. However, it is not always an easy task to locate the main circuit breaker panelboard. This happens for a variety of reasons, including lack of a standard location, remodeling, and additions to home electrical systems. Firefighters may decide they need to shut off all of the breakers in a panel box when they are not able to confirm the location of the main breaker.

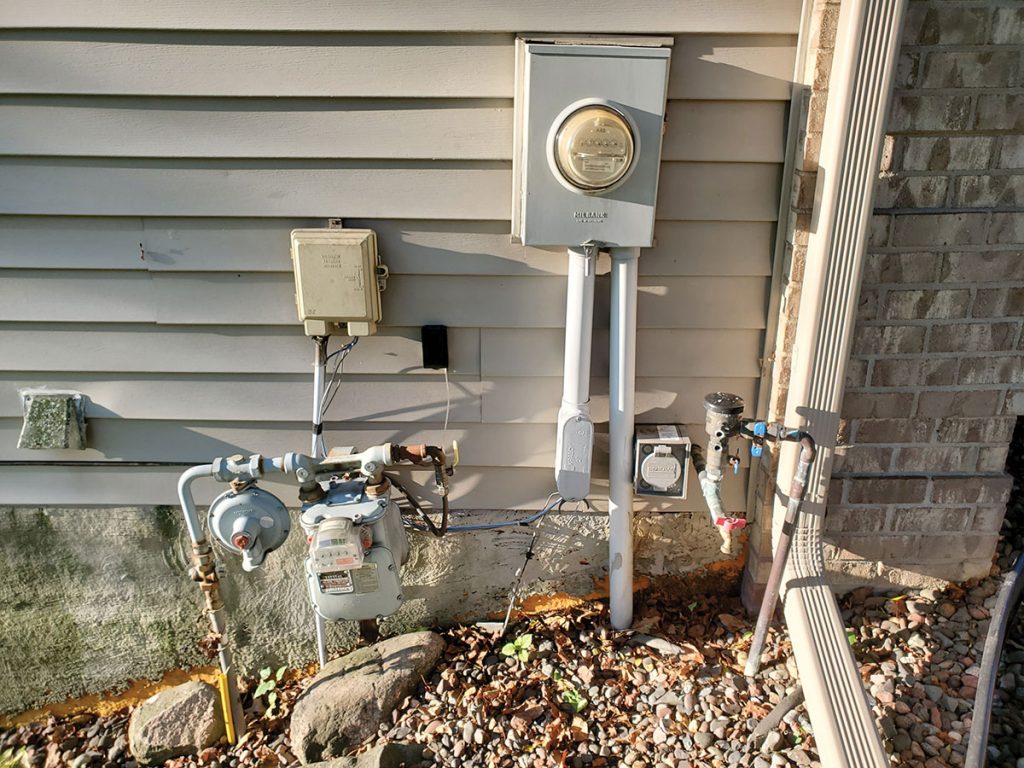

Sometimes firefighters find secondary circuit breaker panels associated with the main panelboard located elsewhere inside the house. However, there is also another possibility due to updates to the NFPA 70, National Electrical Code (NEC). NFPA 70 Chapter 2 now requires that the construction of new one- and two-family dwelling units will have an emergency disconnect installed in an outdoor location. Upgrades to existing electrical service could also likely trigger the requirements of chapter 2. That means an emergency electrical service disconnect will be in a “readily accessible outdoor location.” Emergency disconnects will usually be installed close to the electric meter, making them very easy to find.

The requirement for an exterior emergency disconnect was done first and foremost to provide first responders with a way to quickly and safely isolate electrical power. The need for emergency disconnects is not limited to the traditional power grid. We are seeing an increasing number of options to supplement power from the grid and provide backup power in the event that the electrical supply grid is disrupted. This includes on-site generators, wind electric systems, photovoltaic (PV) power, and energy storage systems such as batteries.

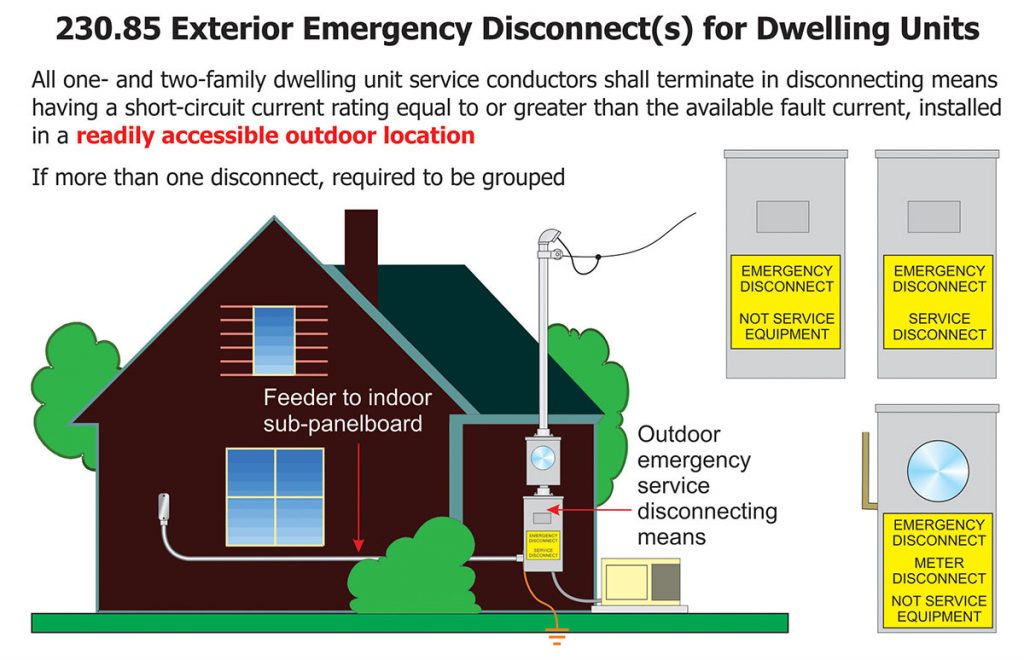

The 2020 changes to the National Electrical Code require outdoor disconnects for all incoming sources of electrical power. They are required to be placed in an outdoor location and be grouped together if more than one emergency disconnect is needed. For example, a home might have solar panels and a backup generator in addition to traditional service from an electrical utility service. In this case, each source of power might have its own emergency disconnect.

Incident commanders should look for the location of gas and electrical service connections during their initial 360 size-up at fire scenes. They should note if there is an emergency service disconnect on the exterior of the building. Doing so will save time and energy for fire crews assigned to secure utilities, including turning off electrical power to the building. It may also reduce the need to turn off individual circuit breakers in subpanels elsewhere in the building. This will provide a much safer scene and allow individual circuit breakers to remain untouched until fire investigators arrive and begin their review of the fire scene.

Historically the best way to disconnect power to a one- or two-dwelling structure was to have a utility worker “pull” the electric service meter. This would ensure that electrical power was disconnected at the service meter on the outside of the building. The NEC-2020 exterior emergency disconnect requirement puts that disconnect in close proximity to the electric meter and should greatly reduce the temptation for firefighters to attempt pulling electric service meters during emergency events.

230.85 Emergency Disconnects. For one- and two-family dwelling units, all service conductors shall terminate in disconnecting means having a short-circuit current rating equal to or greater than the available fault current, installed in a readily accessible outdoor location. If more than one disconnect is provided, they shall be grouped. Each disconnect shall be one of the following:

(1) Service disconnects marked as follows:

EMERGENCY DISCONNECT,

SERVICE DISCONNECT

(2) Meter disconnects installed per 230.82(3) and marked as follows:

EMERGENCY DISCONNECT,

METER DISCONNECT,

NOT SERVICE EQUIPMENT

(3) Other listed disconnect switches or circuit breakers on the supply side of each service disconnect that are suitable for use as service equipment and marked as follows:

EMERGENCY DISCONNECT,

NOT SERVICE EQUIPMENT

Markings shall comply with 110.21(B).

However, it’s still advisable to request that a technician from the electric provider respond to the scene. They have training and tools to detect any stray electricity that may impact the fire scene. At the end of the day, the goal should always be to reduce hazards and protect firefighters whenever possible.

References

- NFPA 1001, Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, 2019 Edition

- NFPA 70, National Electrical Code (NEC), 2020 Edition

Find Us on Socials