Have you seen an electrical installation that stops you in your tracks? We’re talking about those installations that make you laugh and shake your head in disbelief! Others may make you angry that someone risked his safety and the safety of others. You may want to grab a camera and take a photo in order to share your shock or amazement at such an installation. It can be upsetting to find an installation where the installers knew of the hazards, ignored them, and subjected themselves or others to serious injury or death. Laziness, arrogance, ignorance, pride, unwillingness to purchase or install the proper wiring methods or equipment, or disregard for the safety of others all could enter into what occurred.

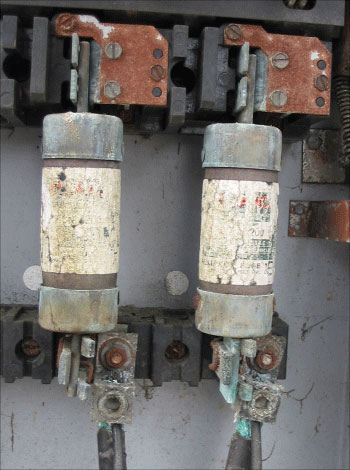

Photo 1

Inspectors will no doubt come across many unsafe installations during the course of their career. The question is, How do they deal with it? This article will discuss recognizing hazards, degrees of hazards, inspector training and support from their superiors. The role of public servants will be discussed, along with management styles, liabilities, when to shut the power off immediately, when to write a correction notice and give some time for correction, and other issues.

Recognizing Hazards

How do inspectors recognize a hazard? Some hazards are obvious, which even untrained persons would recognize. Some basic examples are:

- Exposed live parts

- Severely damaged conductors or equipment

- Used wrong equipment

- Overloaded circuits

- Weather-damaged electrical wires, poles, or equipment

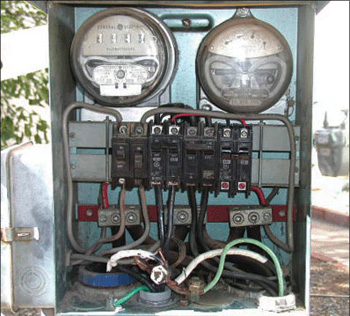

Photo 2. While inspecting de-energized outdoor units and disconnects, the inspector identified a 110.26 working clearance violation.

Other hazards are not as obvious but could be deadly. An example is an old 1940s vintage 240-volt 30-ampere fused outdoor service disconnect installed on a dwelling unit. The homeowner has called an electrical contractor and complained of no heat from his electric hot water heater, and requested an electrician to come check it out. The switch has a metal handle which operates the knife blades of the disconnect. The insulating material which separates the metal bar and operator handle has broken off and this hazard is not visible to the viewer. On first glance, most electrical professionals and many homeowners would think the handle needed to be moved up into the on position toward the wall of the building, in order to re-energize the circuit. However, to do so would result in a line-to-line fault (short-circuit) at the handle of the service disconnect, because the metal bar that is part of the handle would contact both lines of 240 volts via the fuse blades, which could electrocute the person holding the uninsulated metal handle.

This dangerous situation would require immediate disconnection of electrical power. The necessary repairs—at a minimum—would include replacing the service disconnect, assuring proper overcurrent protection, grounding and bonding of the disconnect, and possibly replacing service-entrance conductors and mast, if needed.

There are many more examples that could have the same fatal result.

The worker should be trained and aware of possible electrical hazards. He must be wearing proper PPE and have tools appropriately rated for the voltage. He must turn off the power to the disconnect and carefully open it to investigate the problem before trying to re-energize the circuit.

It must be remembered that not all code violations are unsafe conditions, but all unsafe conditions are code violations.

Training Inspectors

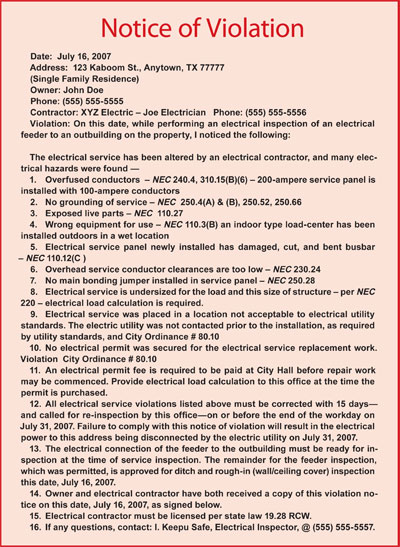

Photo 3. Illegal taps of service conductors, damaged service disconnect has inadequate fault current rating. Overfused conductors, neutral and equipment grounding conductors are not properly terminated. Numerous other violations exist.

Have electrical inspectors received training on how to handle unsafe conditions? Do they know what to look for? Do they have a broad range of electrical experience to draw from, or has the bulk or their experience been in another trade, such as plumbing or building? At this point, it is very important to remember NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace. NEC-2008 draft states that a qualified person is “one who has skills and knowledge related to the construction and operation of the electrical equipment and installations and has received safety training to recognize and avoid the hazards involved.” Do electrical inspectors have the training and experience to recognize electrical hazards to themselves? Do they possess the awareness, safety training and the personal protective equipment needed to avoid the hazard, to protect themselves and others, and to make the right call for the good of all concerned?

Electricity is a wonderful tool when used in a safe and proper manner. If not, it can be a deadly hazard.

Do Electrical Inspectors Have Support?

What kind of backing or support do inspectors have from those in authority over them? Does the inspectors’ supervisor trust their abilities as professionals, have faith in their decisions and ways of working with the customers, and value their judgment?

Who manages or oversees the work of inspectors? Management styles vary. Some code-enforcement managers are truly concerned for public safety, and are willing to address issues and confront persons in a legal and proper manner if there is an unsafe condition. They are willing to do what is right, because it is right, because they genuinely care about safety. They are experienced and knowledgeable electrical professionals. Other managers may not have an electrical background, but do have knowledge and experience in other areas, good common sense, and they work well with electrical inspectors and trust their judgment. This makes for a workable situation and is good for all concerned.

Photo 4. New emergency power system. Ten 1/2? EMT conduits, three phases of 480Y/277-volt circuits installed into a 4? square j-box. Loose wire nuts, conduit connectors and locknuts. Box has no cover and has loose extension rings. Numerous other violation

Other managers or officials may be unaware of, or may not recognize or believe that a safety hazard exists. They may be hesitant to act, or may quickly fold under public or political pressure, or if a customer gets angry or threatening. Perhaps the upset customers are community leaders or government officials that want their work passed, even though it is not up to code. In these cases, complacency and compromise, as well as “enforcement lite” become the name of the game. This can be very challenging for conscientious inspectors. Those who have supportive bosses should appreciate them.

Challenging Times

If the inspectors have a boss that is difficult to work for, they should be under his or her authority as best they can without compromising their integrity, and document, document, document. Some inspectors use a stenographer’s spiral-bound notebook. In some jurisdictions, it may be admissible in court, as the notebook cannot be added to, if the records are kept in neat and chronological order without space in-between to add entries. This is only an observation, and would need to be verified by legal professionals in the inspectors’ locality. If inspectors are instructed by their superior to do something that violates their good conscience, they should explain their views respectfully, provide supporting factual data—Code requirements, related photos, and viewpoints of others whom they may value and respect—and respectfully appeal to their authority. Hopefully, the authority will listen. If not, they may assign the task to others or direct inspectors to approve the installation. Someone has to make the decision and, unfortunately, sometimes inspectors will not like the results. The decision rests with those in authority. It is best for inspectors to be under authority, respect their authority, and work with them the best that they can. If the manager, supervisor, or director makes a decision contrary to what the inspectors would like to see happen, the inspectors need to abide by that decision, realizing that the responsibility for the decision no longer rests with them. An article in IAEI News, “The Authority of the Electrical Inspector,” beginning on page 96 of the January/February 2007 issue, addresses these matters in further detail. It’s always wise for inspectors to think about how they will handle these types of situations before they get into them, and to the best of their ability to make the right call regarding the electrical installation.

Evaluating the Installation

When electrical inspectors become aware of an unsafe situation, there are a number of items to consider, such as:

- How bad are the violations? Is there an immediate danger to life or a hazard to property if the power remains on?

- Does the violation upset inspectors because it isn’t right, or doesn’t meeet the letter of the Code?

- Is it a flagrant violation, or one that simply does not meet the letter of the law but is not a real hazard?

- Was it done in ignorance or because the owner or tenant trusted that the installers knew their stuff and would do it right?

In some cases, the owner or tenant may have hired contractors who were unqualified or dishonest and may have paid them already, and now they have limited or no resources available to correct the unsafe situation.

It is always important to keep personalities out of the picture when evaluating work. For example, inspectors should not write more corrections on work just because the electrical contractor is arrogant, non-compliant, argumentative, and generally a pain to work with.

- Are the violations a result of persons who knew it was wrong and did it anyway?

- Or, the result of untrained persons trying to make the situation safe, but not knowing or asking the right people how to do it correctly?

The motive of installers can be important to know, in order to pass judgment on the installation in an appropriate way. Correct those who are in flagrant violation, but don’t be too strict if the work doesn’t warrant it.

- Was part of this installation acceptable under previous editions of locally adopted electrical code?

These questions may seem immaterial, but it is best to know as much as possible before deciding whether to disconnect the power, how much time to allow for corrections, and if other laws such as permitting fees and licensing laws have been violated. For fairness, it helps to try to ascertain the intent of the persons involved before taking action and passing judgment.

Inspectors must always remember that they are dealing with persons, but also the law, and must exercise their authority judiciously and without malice, with electrical safety as the goal; and they must treat others, as they would want to be treated. It is wrong for inspectors to abuse their authority.

- Was an electrical permit(s) purchased for the work?

- Was the customer aware of the safety concerns prior to this? How were they made aware of the concerns? By whom? What have they one, if anything, to address the concerns?

- What is the permit history for the property? When was the last electrical permit purchased? Was the installation part of that permit? Was the work ever inspected? Did the inspector approve the work at that time? Were corrections needed? Were they completed, and was there a call for re-inspection? Were records kept?

- How did inspectors learn of the violations? Was it during a routine or scheduled inspection, or because of concerns with the electrical installation by the fire department, building department, or by inspectors from other disciplines, a contractor, tenant, or other public or private agencies? Should any of the above named departments or individuals be involved? Sometimes a situation that doesn’t look right electrically could be a fire hazard. Other public health or safety issues may be stumbled upon inadvertently.

- Are insurance adjusters involved?

- How extensive is the damage?

- Does the local electrical law require that if more than 50 percent of the structure is remodeled, refurbished, rewired, etc., that the whole installation needs to be brought up to current Code standards?

Inspectors must be able to give code references for every correction written, and be able to explain to the customer or contractor why the correction(s) are needed, and must write the violation/correction notice so that it is easily understood.

- Did an unlicensed contractor perform the work?

- Will the owner reveal who that person or company is?

Electrical inspectors generally take their job and electrical safety seriously, which is a good thing. Unfortunately, not everyone shares that same level of concern for electrical installations. For example, the customer may have a very dangerous installation and not realize just how dangerous it is, even after inspectors give a good explanation.

A sense of humor may help relax inspectors or customers, but only if appropriate. Let’s face it, a lot of “creative wiring” goes on, and some of it is so outrageous that it can be taken as humorous.

- What time of year is it? In the wintertime, in cold climates, shutting off power to a structure —particularly a home—can be serious business.

- Are any of the occupants of the structure on oxygen or life support equipment? If so, it would be unsafe for the power to be disconnected. Is there another place for the occupants to live while repairs are made?

- If a fire situation, how much of the structure was damaged? Could the structure still be lived in if a qualified electrician disconnected the damaged part of the wiring from the power source? Would this be OK, pending the approval of the fire department and electrical inspector?

Making the Call

There are situations, however, where electrical inspectors must make an immediate judgment call on the installation at hand. Is there an electrical hazard to life and property present? Is it an immanent threat—one that is present or inherent, or is it rapidly deteriorating to the point of becoming a serious hazard? Is it time to call the electric utility and wait on-site until they arrive and shut the power off, or is it appropriate to notify the responsible persons in writing of the violations, and leave? Inspectors must contact the owner, and inform them of the hazard. It may be time to contact the owners and give them a limited number of hours or days to make the needed corrections. Either way, a correction notice or citation must be written clearly and contain all pertinent information.

What to Include on the Correction

Notice/Notice of Violation

It is always important to include the following information on the correction notice or citation:

1. All electrical corrections applicable to the unsafe installation. It is essential—this cannot be over-emphasized—and critically important that inspectors be fair but thorough and include all violations on the initial notice of violation. It is unfair and a disservice to the customer for the inspector to write corrections, have the responsible person make all corrections listed on the initial notice, and then return and write more corrections that should have all been listed on the first notice. This is nearly guaranteed to anger and frustrate the customer.

2. Date and time that the citation was written

3. Address

4. Owner’s, tenant’s, and/or contractor’s information —any and all that apply

5. Telephone numbers of all parties concerned, including inspector’s

6. Party (parties) responsible for the installation or hazard, if known

7. How inspectors came upon the unsafe condition—what duties they were performing when they became aware of the unsafe situation, or if the fire department made them aware of it, etc.

8. What specific code violations exist? Give which code or ordinance, and describe the situation so that even a novice person could understand the hazard.

9. Electrical inspectors’ action; for example, “The serving electric utility was called for an immediate disconnect of all electrical power to the structure,” or something to that effect.

10. State, which, if any, permits or licenses are required to correct the work.

11. If electric power is allowed to remain on at the structure, specify the amount of time the responsible party has to make the corrections and call for a re-inspect.

12. Date that the corrections are required to be completed.

13. Inspectors must clearly communicate orally and in writing that all corrections must be completed as outlined in the notice of violation and that the work must be re-inspected and approved by the AHJ. Examples are before a specified date: electrical power is restored, persons may reoccupy the structure, specified electrical equipment or machinery may be used; or normal functions (business, etc.) related to the electrical system and use of the installation may resume.

People Skills

If corrections are needed to remedy an unsafe electrical installation, or an immediate electrical hazard exists, the manner and demeanor of inspectors as they approach the customer is very important. The inspector’s body language and tone are both extremely important; remember that over 90 percent of what people receive as communication from us is from our body language, and less than 10 percent of what we communicate is through what we say. If inspectors are professional, knowledgeable, and have good people skills, it will make the unpleasant news a little more bearable: the power may have to be shut off, and/or the customer’s time and money will have to be spent. Most customers have hundreds of ideas of how to spend their money, and very few plan to spend it on their electrical system. Inspectors must effectively explain the hazards involved, the threat to the owners’ safety, and their liability if others are injured by their inaction. Many times a fire marshal or battalion chief, fire captain, electrician or electrical contractor may be present as well, which will add credence to what inspectors are saying, and help customers accept the news. It is a good idea for inspectors to speak with fire or other electrical personnel before they approach customers, and thereby present a more unified front. Inspectors should also be careful how customers perceive their role with an electrical contractor. This is advisable, so that customers do not think the contractor willing to fix the problems is in cahoots with the inspectors, or that inspectors will gain from the contractor monetarily or in other ways.

It pays field inspectors to develop great people skills, and handle difficult customers and situations at their level. This is better than taking a hard-nosed, totally-by-the-book and zero-compromise attitude and becoming difficult for customers to talk to or deal with. Safety is the job of electrical inspectors, most of whom are persons of high integrity, who really care about protecting the public and approving only those electrical installations that they know are safe. They are reasonable people who are trying to do their jobs to the best of their ability. Some inspectors out there are on a power trip or don’t really look at the work in an installation. These inspectors enjoy feeling important, but they do their customers a great disservice. Appearing to be tough and abusing their authority are the only ways they know to do their job. For others, the inspection day is one big social event where they drive around, talk to people, and are paid for it. These inspectors are not doing what they’re paid to do, which is to look at the work, know what they’re looking at (or find out), and assure code-compliance for safety.

Some inspectors make their jobs more difficult than they need to be, simply by being unapproachable and hard-to-talk-to or incompatible. It pays to listen to customers and their viewpoints. Information may be shared that will increase their knowledge, or change their viewpoint of the installation.

It is critical to write corrections when they need to be written, and to be prepared to give a bona fide Code reference for every correction. Inspectors must put themselves in the shoes of the owners, contractors, or installers, and try to understand why the installation was done a certain way. However, things are what they are, and the installation is just plain unsafe, and non-compliant. Fine. Write the correction(s) because it is clearly needed. The installer and/or installation have really earned one. Write it.

Sidebar

Enforcement

Just as important as the ability to recognize electrical hazards, and make others aware of them, is how inspectors follow up and gain compliance with the electrical codes which apply to the particular installation. Writing corrections is good, when appropriate, but carries no weight and has no teeth if there is no follow-through. Violations must be corrected as required in the notice, within the timeframe specified. Be sure that the timeframe is appropriate and reasonable, and that it follows the guidelines in the law or inspection policies. Inspectors must bear in mind that a legitimate extenuating circumstance may arise to delay the corrections of all violations, but the corrections still must be completed in a reasonable time, in order to protect persons and property.

We have discussed the need for training and the awareness of hazards, support for enforcement when inspectors write corrections for unsafe installations, evaluating the installation, and some of the many things to take into consideration. We have also discussed making the call, what to include on a notice of violation, people skills and communication, and follow through. Unsafe conditions do exist, and inspectors will come across them. Remember, inspectors have authority; but how are they using it? Hopefully, this article has provided some food for thought as inspectors approach their task of keeping the public safe from the use of electricity.

Find Us on Socials