Few can claim the honor and the privilege of being a decorated war veteran, and even fewer can claim a career in the electrical industry spanning sixty-five years. But what really sets Anthony (Bosco) Rabasco apart is the fact Tony just acquired all three electrical certifications (One- and Two-Family Dwelling, General and Plan Review) within a five-month period—a feat the average person would find challenging at best. But even that seems trivial when you consider Tony has done this at age eighty-one! To understand this man’s inner drive requires a deeper look into the person and the fascinating life he has led.

YOUTH

Born in January 1928, Tony’s youth was cut short by the Great Depression. His father, a self-employed immigrant from Italy, struggled to make ends meet; so even at an early age, the family had little choice but to put him to work.

“As far back as I can remember all I’ve ever known is work. We were poor, like everyone else at that time. I can remember my mother telling me to cut and stack the wood before my father returned home in the evening. My toys were an ax and a saw.”

By age ten, Tony was shining shoes for 10 cents at the New York Central Station in Mount Vernon or out at the race track with a custom-made shoeshine kit constructed by his uncle, a tinsmith. When he wasn’t shining shoes, Tony lugged blocks of ice, drawn by horse and wagon, to homes and four-story walk-ups for 10, 15 and 25 cents respectively.

Later, secured with a $25 bond purchased by his mother, Bosco worked a paper route of 132 newspapers in the afternoons; then he hurried to the local German deli where he peeled potatoes or restocked sodas in the evenings.

“I felt guilty if I didn’t turn everything I made over to my mother. If I made 80 cents, she got 80 cents. On occasion, she might give me back a dime or a quarter for the movies.”

While still sixteen, as the family furnace was being converted from coal to oil, two electricians, the Waldman Brothers, were so impressed with Tony’s curiosity about their trade that they hired him on the spot. Initially, his job was only to watch the truck and carry hand tools for 65 cents an hour; but as time passed, the Brothers brought him in, handed him a brace and bit and told him to start drilling—by hand. In this way, over time, Tony began to learn the trade that would carry him through to the present.

Immediately upon graduating high school in 1947, Tony signed up for the Army where he remained on inactive duty until 1950. During this time, at age twenty-two, he passed his electrical master’s exam for the city of New York and was preparing to open his own business when Uncle Sam came calling. The Korean Conflict was about break wide open.

KOREA

After landing at Inchon, Tony supported an assortment of divisions and battalions as a member of the Signal Corp, a vital communications link between headquarters and the frontlines. But unlike the infantry, the Signal Corp was highly specialized and severely undermanned. Instead of the customary fifteen-day rotation for those on the front lines, members of the Signal Corp would often see combat duty lasting from one to two months.

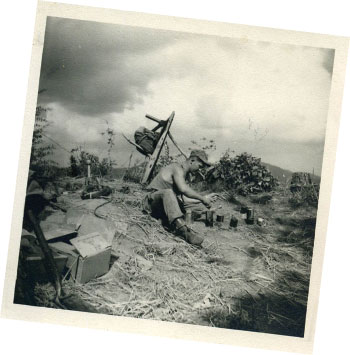

Photo 1. Korea, 1951. Tony (Bosco) Rabasco crouches over another cold dinner of field rations.

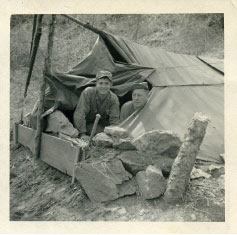

“We’d climb to the highest ridge to transmit and receive radio signals. Even though the weather and temperatures were extreme and unbearable, being alone in a hostile environment was worse. Being alone was torture—so difficult to deal with. We had no idea when we might expect to be relieved. At night the mountains would tremble from the effects of artillery shelling. We shivered from the cold and from fear. And as the frontlines jumped (moved), so did we. That meant carrying a tent, a sleeping bag, food, water, a weapon and a generator for the radios that alone weighed fifty-five pounds.”

To this day, Tony swears his years of hard work gave him an edge over his fellow soldiers. “Other guys were cracking up all around me, but my ability to withstand hard work and my faith are what made the difference. I really believe my childhood years served me well and are what brought me through the war in one piece.”

Food was always an ongoing concern—it had to be scrounged from nearby units; and, even then, it was often unheated field rations. But water was the most difficult—five gallons of water (approximately 45 pounds) had to be hiked up the ridge under the threat of enemy fire, and it had to last the three-man team one week. All totaled in the first year, Tony bathed maybe five times.

Like so many soldiers over so many centuries who fought in winter conflicts, Tony suffered frostbite on both feet. A note was entered into his medical record at a field hospital, but that was the last he would hear of it for the next fifty-five years. In the summer of 1951, he also contracted malaria, requiring treatment in Japan. Upon feeling better, Tony awarded himself a night on the town by sneaking off base in the trunk of a car, a stunt that immediately landed him on a plane back to the frontlines.

ELECTRICAL CAREER

“In 1953, I saw my first electric drill. What a timesaver that turned into! But driving to the job was nothing like it is today. We had panel trucks where we sat in the back on milk crates, along with all the material and tools. You felt beat up before the day even started!”

Along the way, Tony began picking up pieces of real estate with profits from his share of the business. In fact, two of these properties Tony still owns and maintains today—all by himself. He also built an entirely electric house for his new wife and soon to be family of four boys.

Unfortunately in 1973, the twenty-year partnership of Metro Electric disbanded. Wasting no time in order to preserve accounts, Tony immediately reorganized into Bosco Electric, as sole owner and operator. Business skyrocketed under his direction for the next fourteen years. But in 1987, urban renewal dealt Tony an unwarranted blow by claiming the building that housed both shop and offices. Now fifty-nine years old and facing the prospect of picking up the pieces again, Tony pondered his next move. Life’s whimsical and mysterious ability to open and close doors was about to swing itself wide open. Little did Tony know that his career in the electrical industry was just beginning!

THE INSPECTOR

Dick Tyrell, then chief electrical inspector, Westchester Division, New York Board of Fire Underwriters always had his eye out for talent. “In those days, qualifications to become an inspector were based more on personal character and less on accreditations and certifications. We hired Bosco because we knew him to be a successful contractor with a master’s license, good solid knowledge of theCode, and well-respected among other contractors. That was good enough for us.”

“To break a new guy in, we’d pair him up with a seasoned inspector for up to six months until he felt comfortable enough to go solo. Then he would be assigned an area.”

Not limiting his involvement to just his new duties, Bosco threw himself into everything that was related to IAEI, which he had joined in 1967. He became a regular fixture at dinners, meetings, seminars, and held the post of master at arms for over twenty years.

As an inspector, Tony was a quick study and within two years he was reassigned to the city of White Plains as sole inspector where he would remain for the next fifteen years. These were boom years for White Plains—three major shopping malls, office buildings, towering condominiums, a new train station, schools, hospitals, renovation of the high school and so much more.

NEW YORK ELECTRICAL INSPECTION SERVICES

A firm basis inCodeknowledge, although essential, is no longer sufficient in New York as an electrical inspector. Cities and towns now require tested verification in the form of three certifications. This applies equally to everyone, including Tony.

“I wasn’t ready to leave the industry so I started studying in 2005 with the help of Pierre Belarge of ETS. He allowed me to sit in on evening classes; but from the beginning, I struggled with the computer.”

Overcoming this obstacle would require a plan. Every morning by 6 a.m., Tony would arrive at the office and quiz himself at various online sites. He spent hours reviewing late into the night, and would then bounce questions off other inspectors the following morning. Although the demands of business continually interrupted the study process, by 2009 he felt primed and ready.

Nick Morabito, president of NYEIS, commented on Tony’s fortitude: “Once Bosco sets his mind to something, it’s a done deal; it’s that simple. He’ll block everything else out and just lock onto the goal until he achieves it. And he’s been this way since the first time I met him and hasn’t changed one bit.”

On March 9, 2009, Tony passed Electric General, followed by One- and Two-Family Dwellings on April 6. Finally, on August 10, 2009, Tony completed the trilogy with Plan Review.

RETIREMENT?

It goes without saying, Tony has graciously refused Time’s offer to mellow into his golden years. On the topic of retirement, Tony said it best, “I don’t even want to hear the word! I enjoy being among the fellows, going to meetings, visiting jobsites and learning ofCodechanges. And I’m not in this for the money. My reward is being among the tradesmen.”

Albeit Tony’s workweek is now three days, he is still the first in the office every morning and he stays if needed. Tony has even been back to White Plains recently to fill in. Interestingly, two of his sons went on to military careers and the other two are associated with the electrical industry. And the backbone behind it all, Bosco swears, is his wife, Rosa.

In 2008, on a visit to the VA hospital for an ear infection, an aware VA staff member uncovered a glitch in the Army’s record keeping regarding Bosco’s frostbite. Now, fifty-five years later, Bosco has started to receive a sizable monthly check to compensate for all those forgotten years.

Is Bosco still bitter? On the contrary; for the past eight years on the anniversary of the Marines, Bosco makes a trip up to West Point where he speaks to the cadets on his experiences in Korea. Even though his time in Korea continues to be the defining event in his life, Bosco’s list of accomplishments as an inspector remains an ongoing process. One has to wonder what other achievements Bosco is capable of adding to that list.

Find Us on Socials