This article deals with abandoned, low-voltage communications cabling in building structures, and the serious fire hazard concerns that prompted the 2002 National Electrical Code to require the removal of abandoned cable. The article was written with the goal of encouraging electrical inspectors and other AHJs to enforce code compliance.

In just the past 12 months numerous training and educational seminars have been held by industry trade organizations. Several major safety companies, riser management firms and responsible contractors now offer solutions for the removal of abandoned cable. Building owners, property managers, and the like, are being encouraged to take action in advance of compliance inspections to assess and put in place a removal plan for abandoned cables. Electrical inspectors also need to be brought up to speed.

The Problem

Abandoned cable presents several problems. The large volume of accumulated cable not in use may prevent the installation of new cabling because of completely overfilled cable conduit pathways and spaces. Abandoned cable also may severely restrict airflow in ceiling cavity plenums. For these reasons, its removal may become a practical necessity. In fact, this is often done. During a major renovation when the building floor is gutted wall-to-wall, all low-voltage network and communications cable is removed.

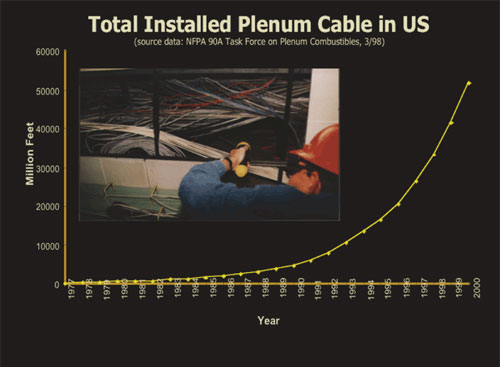

Figure 1. Total installed plenum cable in the U.S.

However, the most serious problem from abandoned cables being allowed to remain in the structure is their potential to both fuel and spread a very large, very hot fire in concealed spaces, in the event of a building fire. Also large amounts of smoke are generated making the fire extremely difficult to find and fight. Over the years many types of cable made from a variety of materials have been installed, including 25 pair PVC telephone cable and IBM type cable. The fire spread problem is further exacerbated when firestopped penetrations are disrupted and are not adequately replaced or protected when new cabling is installed in the same pathways as the old.

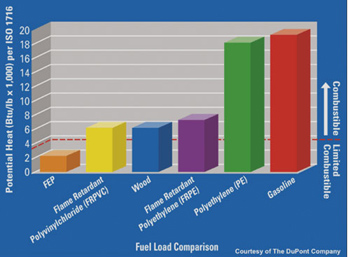

Figure 2. Potential heat of cabling materials

Over half the weight of today’s typical 4 pair UTP (unshielded Twisted Pair) cable is comprised of plastic insulation and jacketing materials. For example, the installation of 100,000 feet of typical 4 pair UTP data cable places approximately 1200–1500 lbs. of exposed plastic materials in concealed spaces, when installed outside of conduit as permitted by the NEC. An average, large commercial office building can contain tens of thousands of pounds of plastic materials as part of the in-use cable infrastructure. Some of these plastic materials are engineered to resist high heat, flame spread and smoke generation, while others are not. Now add one or two layers of abandoned cable and even more, perhaps orders of magnitude more, plastic material is imbedded in the structure adding to potential fuel load depending on materials used. Compared to power cable, most of the combustibles in concealed spaces come from communications cabling. It’s easy to see why the combustibility or fuel load of remaining abandoned cable materials is so critical, and why abandoned cable should be removed.

NFPA Codes and Standards

Figure 3. Simulation of full-scale plenum fire

Several devastating and tragic fires during the mid-to-late 70s, such as the MGM Grand in Las Vegas and the 1979 World Trade Center fire in New York, gave rise to new provisions in the NEC which required that new low-voltage cables installed in buildings be listed as to their flame spread and smoke generation characteristics. For example, only CMP type communications cables are permitted in ceiling cavity and raised floor plenum spaces. While this has been a major step forward in improving fire safety, the problem is still with us … and we can do better.

According to the NFPA, there are, on average, 5800 fires in office buildings of six stories or more every year—2.5 fires every day! In recent years several of these office building fires, such as the 1996 Rockefeller Center fire in New York and the One Meridian Plaza fire in Philadelphia in 1991, along with many others, dramatically displayed the potential hazard from low-voltage communications cables, both abandoned and in use.

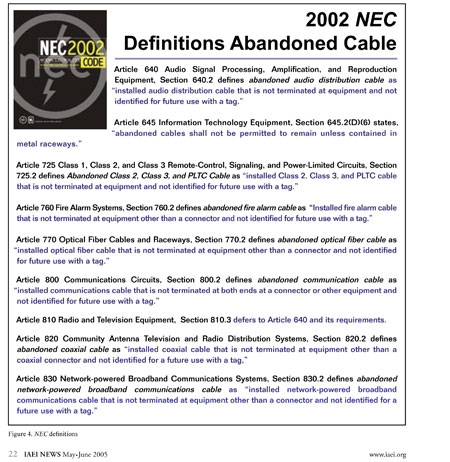

Figure 4. NEC definitions

It should be noted that NFPA statistics and fire investigation reports do not explicitly attempt to target the role of communications cables in the spread of these fires. However, after studying the fire investigation reports, it is very clear to this author that we can construct a basic, empirical understanding of the mechanism of fire spread in many of these fires where cabling was involved. The ignition source for many building fires is electrical in nature, from overheating and electrical shorts. This clearly does not occur with low-voltage cabling, as there is insufficient energy to cause ignition of combustibles. However, since bundled communication cables are typically installed in the same risers and pathways near or adjacent to power cables, the large amounts of low-voltage cabling are quickly exposed to the fire. As shown above, some of the materials used in these cables can behave as a solid fuel, spreading the fire vertically in the risers and horizontally across ceiling cavity plenums.

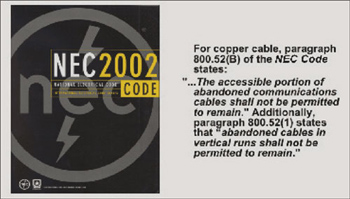

Figure 5. NEC cable removal

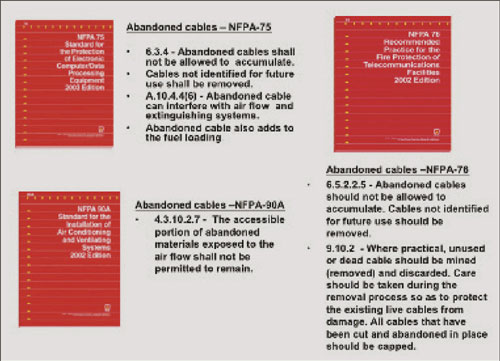

With the publication of the 2002 NEC, the NFPA finally took long overdue action and addressed the problem. The buildup and accumulation of combustibles from abandoned cable mandated action and code compliance to help alleviate and mediate the significant increase in occupancy fuel loads. Other NFPA codes and standards followed suit and took action on the growing concern over fuel load by correlating with the NEC and issuing similar provisions for the removal of abandoned cable. But actual enforcement of cable removal can be problematic, particularly in buildings when permits are pulled and business operations continue during new cable installation projects. There may be subjective judgment calls inspectors will need to make concerning what is considered “accessible,” and whether cable “tagged for future use” is in fact accurate or is it a ploy to take advantage of a loophole in the Code.

As of this writing the NFPA 90A committee responsible for the 2005 NFPA 90A Standard for Air Conditioning and Ventilation Systems is considering even broader reform to address the cable fuel load issue for both abandoned and new cables added to buildings. NFPA 90A has jurisdiction over the flame spread and smoke requirements for materials (cable) exposed to the air flow in ceiling cavity and raised floor plenums, while the NEC has jurisdiction over the installation of those cables and wiring methods. Ideally these two important documents should correlate, and in the case of removing abandoned cable, they do.

For years, 90A allowed the installation of plenum approved listed CMP cable. However, this cable type was allowed as an exception to the primary 90A requirement of “”limited combustible”” for all materials exposed to the airflow. It comes as a surprise to many that CMP cable, while a decided improvement in reducing flame spread and smoke in ceiling cavity and raised floor plenums, is in fact combustible and can generate up to 17 times more smoke than the maximum allowed by the limited combustible requirement in 90A. What this means for code officials and for contractors who install cabling systems is that codes and cable types will have to be examined more carefully to determine what cables are, in fact, code-compliant and permitted to be installed in the first place.

Figure 6. NFPA Standards 90A, 75, and 76

The 2005 NEC contains a fine print note (FPN) that refers users to NFPA 13, Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems “for requirements for sprinklers in concealed spaces containing exposed combustibles.” Under current NFPA definitions, exposed CMP cables are combustible and have been assumed to be code-compliant for all concealed building spaces. That may not be true. NFPA 13 does not require that buildings be sprinklered. However, when buildings are sprinklered under NFPA 13, sprinklers are required in certain concealed spaces, such as ceiling cavity plenums, when unprotected combustible materials are present. The NFPA 13 Handbook on Automatic Sprinkler Systems provides commentary and guidance on what are considered “”combustible materials.”” In addressing the requirement for sprinklers in concealed spaces, the Handbook states that these spaces “… can contain combustibles associated with building system features such as computer wiring…” (e.g., CMP cables [author’s note]). Sprinklers are not required if cables are put in metal conduit. Sprinklers are not required if exposed limited combustible cables are installed outside of conduit. The latter is by far the most cost effective, safe solution for building owners.

It remains to be seen whether newer, limited combustible cables, designed to meet the original intent and requirements of both NFPA 90A and NFPA 13 will eventually find their way into the NEC.

The Challenge for Electrical Inspectors

The scope of responsibility and breadth of code knowledge needed by electrical inspectors are enormous and difficult challenges. Hopefully, this article sheds some light on the necessity to enforce the removal of abandoned communications and other low-voltage cabling in buildings where mandated by Code. As learned from many fires where low-voltage cables contributed to the spread and intensity of the fire, cable fuel load can be a major hidden hazard. Enforcement of code requirements to remove abandoned cable is not just good construction practice, but an important life safety issue. When it comes to fire protection there is no room for error.

Find Us on Socials