May is National Electrical Safety Month, an annual effort to help reduce electrically-related fatalities, injuries, and property loss—both in the home and at work. Sponsored by Electrical Safety Foundation International (ESFI) and other groups, the goal of Electrical Safety Month is to increase public awareness of the electrical hazards in the workplace, at home, school, and at play. One of the core values of IAEI is electrical safety and one of our primary objectives is to increase awareness of the common electrical hazards that can exist in homes. This includes encouraging consumers to arrange for the installation of ground-fault circuit interrupters in residential applications. In addition to home safety, electrical inspectors and other industry professionals can also work to promote workplace safety both at work and out in the field to keep their businesses healthy and safe.

Safe Work Practices

Electrical workers are expected to possess the required knowledge of safe work practices while working in the field. A firm understanding of electrical installations from rough wiring to finished energized electrical systems and the electrical hazards associated with each is required. Safety rules become more extensive and more demanding when inspectors work around energized equipment, and the inspector should understand the dos and don’ts when working with energized equipment.

Suitable personnel protective equipment (PPE) is required when working on or near energized equipment. In many jurisdictions, the contractors have the responsibility to make it a safe environment for inspection and may be required to provide the appropriate PPE. When working on non-energized equipment, the circuit disconnecting means should be locked in the open position for safety and inspectors should follow all applicable locking and tagging rules. Covers should not be removed from energized equipment unless the equipment is first disconnected from the source and no work is performed before there is verification that the equipment is in an electrically safe working condition.

In the first stages of construction, inspectors are rarely exposed to energized equipment. Projects near the final stages usually have energized equipment and circuits, and jurisdictions often have regulations that require approval or acceptance by the inspector before turning equipment or circuits on. Inspectors should incorporate the same safe work practices that electrical workers do before exposure to energized parts; Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) rules are the same for both the inspector and the worker.

Providing safe access to the equipment for the inspector to perform the job is generally the responsibility of the contractor/owner. However, being qualified also means that one understands the risks and hazards involved and knowing when to ask the right questions before inspecting equipment. In Canada, the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOSH) operates as OSHA does within the United States, and local occupational health and safety regulations and acts specifically mandate safe work practices around energized electrical equipment.

NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace & CSA Z462, Workplace Electrical Safety

The employer is required to provide a workplace that is free from recognized hazards that are or can cause death or serious physical harm to employees. This is especially challenging for inspection agencies and their inspectors as an electrical inspector can face many different levels of electrical hazards on any given day due to the visiting multiple worksites. When you really think about it, an electrical inspector’s workplace can be an entire city, county, town or state so the best protection method is to arm the electrical inspector with the skill and knowledge to: recognize the electrical hazards, understand the injury they present and the necessary safe work practices to employ to reduce the likelihood of injury or death.

National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace, and CSA Group’s Z462, Workplace Electrical Safety, contains requirements for safety-related work practices, considering the condition maintenance of electrical equipment and systems, and safety provisions for special equipment to reduce exposure to electrical hazards. CSA Z462, used in Canadian workplaces, and NFPA 70E are updated in parallel for harmonization of safe work practices.

NFPA 70E begins with a roadmap similar to OSHA’s, i.e., the employer provides the policies and procedures, the necessary equipment, and the training for electrically safe work practices. Once trained by the employer, the employee is required to implement the safe work practices out in the field. NFPA 70E and CSA Z462 provide prescriptive pathways to meet the OSHA and CCOSH requirements to protect electrical workers from electric shock, electrocution and arc flash by providing a four-step approach to electrical safety.

This method includes: establishing an electrically safe working condition, having an energized electrical work permit when working on electrical equipment can be justified, having a written plan for performing energized work safely, and using personal protective equipment as indicated in the hierarchy of controls.

Performing an arc-flash and shock-risk assessment are two of the critical compliance steps outlined in NFPA 70E and CSA Z462.

The arc-flash risk assessment is used to determine the arc flash hazards, to estimate the likelihood of occurrence and the potential severity to injury or damage to health, and to determine if additional protective measures are required including personal protective equipment (PPE). If additional protective measures are required they are implemented in accordance with the specified hierarchy of control (elimination, substitution, engineering controls, awareness, administrative controls, and PPE). If the additional protective measures include the use of PPE, then the appropriate safety-related work practices, the arc flash boundary and the PPE required to be worn by personnel working inside the arc flash boundary are required to be determined.

The shock risk assessment will identify the shock hazards, estimate the likelihood of occurrence of injury or damage to health and the potential severity of injury or damage to health determine if additional protective measures are required, including the use of PPE. If additional protective measures are required, the same hierarchy of control methods noted above is required. If additional protective measures are required, then the voltage to which the worker will be exposed, the boundary requirements, and the PPE necessary to protect against the shock hazard must be determined.

Determining if there is an arc flash hazard and, if so, the necessary PPE is a challenging task for electrical inspection agencies and electrical inspectors, to say the least. The reality of it is the necessary information from a detailed arc flash study or for using the PPE Category Tables in NFPA 70E and CSA Z462 are not always available when performing electrical inspections outside of the large industrial settings; and when the information is available, the electrical inspector may not have the required PPE. For these reasons, the best protection may be to provide sufficient training for the electrical inspector to be able to identify and understand the electrical hazards and their associated injuries, and to establish safe-work practices that do not allow the electrical inspector to be exposed to an electrical hazard

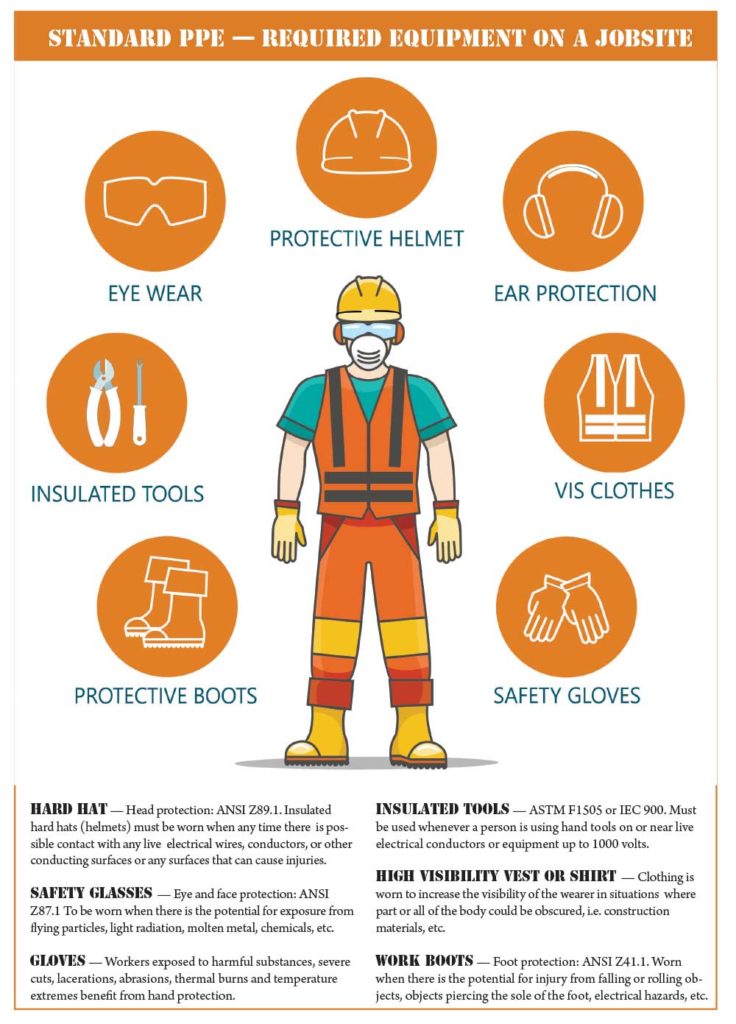

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is arc-rated clothing and other protective equipment worn to minimize exposure to hazards that may result in serious workplace injuries or death. This equipment includes items such as heavy-duty leather gloves, arc-rated gloves, rubber insulating glove with leather protectors, safety glasses or goggles, heavy-duty leather shoes, ear canal inserts, voltage rated hard hats, etc. “Inspection” was introduced into the scope (90.2) of the 2012 edition of NFPA 70E, therefore, identifying that electrical inspectors need to utilized safety-related work practices, including wearing PPE when appropriate. When working where there are electrical hazards, the inspector should have the appropriate PPE that will afford the amount of protection necessary in the event of an incident. Wearing the PPE does not mean that an individual would not be injured from an arc-flash event, it just improves the chances that any burns or other injuries are curable and survivable.

NFPA 70E, Electrical Safety in the Workplace (www.nfpa.org/70E), OSHA requirements (https://www.osha.gov/law-regs.html), and CCOSH requirements (http://www.canoshweb.org/) help detail when and where PPE needs to be worn. These documents provide requirements and guidance about PPE; there is also information about PPE at both the NFPA and OSHA websites. Many organizations offer PPE for the electrical contractor, but it is critical to verify that the equipment has the appropriate arc ratings and is tested to proper ASTM standards.

Electric Shock Protection

Potential shock hazards can be difficult to recognize to the untrained or inexperienced eye on job sites and, particularly, in areas that have experienced storm damage. Electrocution is a result of encountering a lethal amount of current. Shock protection comes in many forms, with properly installed ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) being that last line of defense of protection.

Electrocutions were the fifth leading cause of death from 1980 through 1995, based on data from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)’s National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities (NTOF) surveillance system. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported that the total number of electrocutions in the United States has decreased by 40% from 670 in 1990, to 400 in 2000. During this same period, an estimated number of electrocutions related to consumer products dropped by 44% from 270 to 150 during this same period. The work we do in codes and standards is driving these numbers in the right direction (Domitrovich, March 2013).

Numerous documents detail how to avoid coming in contact with energized conductors and equipment, such as NFPA 70E and CSA Z462. The National Electrical Code, NFPA 70, and the Canadian Electrical Code also contain valuable safety information in respect to arc flash hazard and references in Appendix B Note on Rule 2-306 CSA Z462, ANSI/NEMA Z535.4 and IEEE 1584 as the standards that provide necessary guidance and assistance on this subject.

In Conclusion, Assess Your Work Safety Habits

Here are a few questions to ask when assessing electrical safety within the workplace.

- Is there justification for working on the equipment while energized? If yes, does the installer or inspector wear the proper protective equipment while performing that task?

- Is the level of PPE to be worn understood by the installer/inspector?

- Does the employer know that installers or inspectors work on equipment while it is energized?

- Does the employer understand OSHA regulations about working on energized equipment?

- Are panelboard covers removed when the panelboard is energized? If yes, then has the task been justified? Have the appropriate hierarchy of controls have been considered? If the protection requires PPE, is it worn while performing the task?

- Do the electrical workers know the difference between a curable burn and one that is not?

- Does the worker understand the definition of the term qualified person in Article 100 of NFPA 70E or CSA Z462? Are they considered a qualified person and do they know the limits of their qualifications?

A good indication that more training is needed is if all or most of the answers to these questions are no. Several organizations provide information and safety training in these areas, including the IAEI. In addition to education and training, organizational and individual awareness of hazards and the protective measures needed to avoid the risks is also important. It is important that electrical workers understand the importance of respecting the power and danger of electricity.

Resources

Domitrovich, Thomas A., “Personal Protective Equipment (PPE),” IAEI Magazine, September/October 2014.

International Association of Electrical Inspectors. Becoming the Electrical Inspector. Richardson, Texas: IAEI, 2017.

Johnston, Michael, “Electrical Inspector Workplace Safety,” IAEI Magazine, May-June 2003.

National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 70: National Electrical Code®. Quincy, Massachusetts: NFPA, 2017.

National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 70E: Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace®. Quincy, Massachusetts: NFPA, 2018.

CSA Group. CSA Z462: Workplace Electrical Safety Standard. Toronto, Ontario: CSA 2015

Find Us on Socials