Electricians in New York City are confronted daily with a specific set of hazards, namely exposure to live conductors and energized parts. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), an estimated 350 electrical-related fatalities occur annually, averaging out to approximately one per day.

As far back as 1976, a newly incepted OSHA recognized these hazards to be separate and distinct for all other known construction hazards. The agency requested the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) to assist in preparing a specific standard “…that would serve OSHA’s needs and could be expeditiously promulgated through the provisions of Section 6(b) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act.” Three years later, NFPA produced the first version of NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace, which has since grown to become the gold standard for electrical safety worldwide. Second best in sales to it is the National Electrical Code (NEC).

Electricians are no more exempt from recognized hazards at job sites than all the other trades. Falls, without a doubt, continue to top the list of hazards followed by trench/excavation collapses, unsecured material, and improper scaffold erection.

For example, in 2017 two New York City electricians fell while working from an articulating boom. Both men were 45 years of age and fell more than 30 feet. One was pronounced dead at the site. The other suffered serious head and torso injuries and was rushed to the hospital. It was reported that both men were wearing safety harnesses, but neither had secured their harness to the basket tie offs.

Falls are not the only killer. There is the case of a 53-year-old electrician working in Hell’s Kitchen (a Manhattan neighborhood) who was crushed to death while trying to free himself from a stuck elevator that unexpectedly lurched upward. The father of five had returned to the job site after leaving work on a Saturday afternoon in order to retrieve an item he left behind for his son’s birthday party. He never made it to the party that evening.

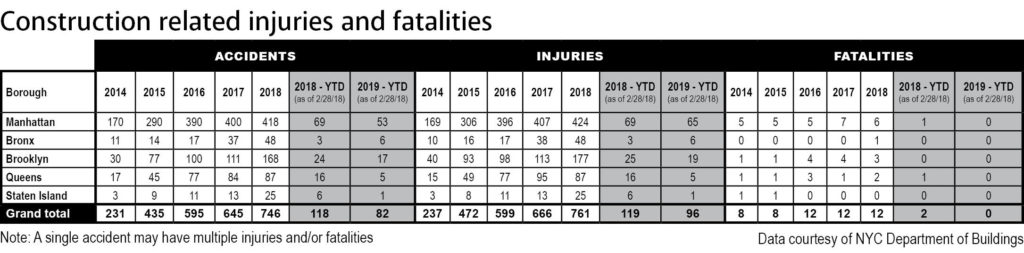

These are not two random events. Rather, they underscore a more systemic problem. Over the past decade, these fatalities and accidents highlight what too many safety professionals already know: that the building boom comes with a terrible price and a dubious distinction.

New York City has become one of the most dangerous U.S. cities in which to work construction. In fact, according to OSHA, construction fatalities in New York City have increased steadily year after year since 2013, and the trend shows no signs of slowing.

A proactive city council

In response to these rising statistics, the New York City Council introduced a controversial bill in January 2017 titled, Intro 1447-C, requiring every NYC construction worker involved in a project three stories or higher to obtain 59 hours of safety-related training in advance of receiving a Site Safety Training (SST) card. This card would be required to be in the worker’s possession in order to set foot onto a construction site.

Although everyone agreed on the importance of safety, opposition groups representing minority workers and their contractors rose to challenge the severity of the proposed legislation. Rallies—both for and against 1447-C—were held in all five boroughs as the debate contentiously raged on.

As the summer of 2017 wore on and the death and accident totals racked up, Bill 1447-C slowly wound its way through committee. Compromises emerged, fostered by council members sensitive to all relevant issues. “We addressed all of the issues that were brought to us: union, non-union, REBNY (Real Estate Board of New York), day laborers. This was not a rush job,” said council member Jumaane Williams, one of the bill’s primary sponsors, in a press conference.

On October 16, 2017, the New York City Council passed Local Law 196, the new title of former Bill 1447-C. Phased in over an elongated timeline, this unprecedented, first of its kind legislation will impact two groups. Group one is all general construction workers who will be required to undergo 40 hours of safety training in order to obtain the SST card. The other group consists of construction supervisors who will need 62 hours of safety training to obtain the card.

For many, the urgency of this bill did not come soon enough. One week after the passage of LL196, two workers plunged to their deaths only hours apart on the same day at separate sites in Manhattan.

Immediately following its adoption, the building commissioner, as required by LL196, convened a 14-member task force to provide recommendations by no later than March 1, 2018, on the nature of the required training. Exemptions from these training requirements are extended to delivery persons, professional engineers, registered architects, and workers at sites requiring only minor alterations or 1-, 2-, and 3-story family homes.

These requirements dovetailed with the same definition for new or existing building, known as a “Major Building.” In order for the job site to fall under the scope of LL196, it must meet the Department of Buildings (DOB) definition of a “Major Building.”

*Section 3310.2, New York City Building Code

MAJOR BUILDING: An existing or proposed building:

1. 10 or more stories or

2. 125 feet (38,100 mm) or more in height, or

3. an existing or proposed building with a building footprint of 100,000 square feet, or

4. an existing or proposed building so designated by the commissioner due to unique hazards associated with the construction or demolition of the structure.

Earning the SST card

Training on an assortment of specified safety topics will be phased in for workers as an inclusive three-part strategy:

Phase one: By March 1, 2018, all workers must have a minimum of 10 hours training, most commonly in the form of an OSHA 10 card.

Phase two: By June 1, 2019, all workers must have at least a Limited Site Safety Training Card which includes a minimum 30 hours of training.

Note: The original drop-dead date for Phase two was December 1, 2018, with a provision for a fallback date to June 1, 2019. New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) exercised that option due to the lack of trainers and facilities, industry-wide.

Phase three: By September 1, 2020, all workers must have at least a full SST card supported by 40 hours of training which means they have fully met the requirements of LL196.

The new law provides a series of choices available to construction workers, but the most popular—due to its simplicity—has been to opt for an OSHA 30 card, which will meet the requirements of a Limited Site Safety Training card.

Assuming all goes to plan, by September 2020, the only remaining requirement for workers is the final 10 hours of training—an eight-hour fall-protection course coupled with a two-hour drug and alcohol awareness training. Having fully satisfied the 40 hours of required safety training, the applicant will then be qualified to receive their full SST card.

Following the completion of this program, workers will be additionally required to take an eight-hour refresher course every five years to maintain the SST card.

A diversified curriculum of 35 topics has been assembled: 18 prescribed courses and 17 elective topics.

“The curriculum also incorporates electives, which allows workers to take courses that may be relevant to the work they engage in,” said Andrew Rudansky, senior deputy press secretary for NYC Department of Building. “For example, there are elective courses that can be chosen related to asbestos-related work, welding safety, excavation work, steel erection, and working on man-lifts. This way, each construction worker can tailor the training to what information is most useful to their job, and an electrician will not be required to take a class on flag person safety. After considering all of these factors, the Department determined that 40 hours was the appropriate amount of training for workers.”

Beginning slowly in summer 2018, then gaining momentum into the fall months, a rush to OSHA 30 training placed a huge demand on 30-hour classes throughout New York City. [OSHA does not permit more than 40 trainees per class.] This forced providers to squeeze in additional classes and created a shortage of trainers citywide who were qualified to administer these courses.

OSHA only permits a maximum of 7.5 hours of training per day. So, this makes OSHA 30 a minimum 4-day class. The majority of these classes have been held on consecutive Saturdays and Sundays which requires workers to sacrifice back-to-back weekends. As the next major milestone rapidly approaches, it is anticipated this phenomenon will only intensify in the months leading up to June 1, 2019.

The teeth of the program

Applicants for building permits at “major building” sites will have to certify to the DOB that employees under the permit will be in possession of the requisite training. If DOB discovers there are workers under the permit who have not received their training, violations with civil penalties can run as high as $5,000 per worker at the site. A provision for mitigation of the fine is provided if the employer sponsors training for their untrained worker(s) within a specified amount of time.

Additionally, the maintenance of a log is also required to document the current status of each site employee’s compliance with LL196. Failure to maintain such a log comes with a $2,500 civil penalty to the contractor/employer.

Sites known to use untrained workers can expect unannounced spot visits from pursuing DOB enforcement officers in support of the penalties.

Presiding over this unprecedented boom is Rick Chandler, NYC building commissioner, whose sweeping changes include 150 more technical staff members, streamlining plan review and the permitting process, a total revamping of the DOB website, and beefing up enforcement with 230 new inspectors. A division within a division is the building enforcement safety team (called BEST Squad), which responds to safety violations, accidents, and injuries on major construction sites, as well as issuance of summons, violations, and stop work orders. It is also charged with the enforcement of LL196.

With change comes challenges

There are many growing pains facing New York City as it continues to phase in LL196. It’s hard enough to wrestle with publicly glaring issues of implementation and enforcement, but the pressure is more compounded when the eyes of the world are on you during the process.

The word is spreading to other metro areas faced with getting a handle on safety compliance issues. The eyes of other building departments have turned to watch these events unfold with close scrutiny.

“NYC has long been an international leader on development and construction safety, with the staunchest and most comprehensive regulations in the country,” Rudansky said. “Regulations that were created in NYC are regularly adopted in cities around the globe.”

One criticism aimed at LL196 by industry leaders is the lack of definitions—a common format found at the beginning of many codes and standards. For instance, LL196 fails to describe who qualifies as a “worker.” The DOB countered by releasing a series of notices giving assorted examples of a “worker” within the context of LL196.

The specifics of what constitutes “training”—which this law so vigorously enforces—is also left vague and undefined. Another noted criticism of LL196 is the largest section within the body of the law dealing solely with penalties and fines that leaves a sour taste to some of its designers’ real intents.

“There have been many gray areas in the updated law, and the lagging clarification makes it challenging to teach workforce appropriate steps to remain in compliance,” said New Line Structures Safety Director Steve White. “The possibility of deadlines getting pushed back causes confusion within the workforce, which is why New Line Structure’s project sites stand firm regardless if the enforcement date gets delayed.”

A mixed response from the field

Site Safety Manager Walter Bullross works on a large 29-story project in Queens. He believes the introduction of LL196 is a good thing for the industry.

“Contractors will continue to push all subcontractors and workers to meet and comply with LL196,” Bulross said. “But it is definitely unrealistic to think contractors will deliberately hurt themselves financially to meet a rule enforced by the DOB.”

Walter Haass, safety director for the contracting firm Hudson Meridian has a differing point of view. “Training is great, but it is not the one fix all. Treating safety as a value rather than a priority is where the industry needs to start. Priorities change; values don’t. I’m not confident mandaory training is going to be the answer that makes the change.

“While we have been proactively working with our subcontract base to comply with the schedule requirements, SST providers and curriculums have still not yet been approved,” Haass said.

Most electrical contractors who were surveyed for this article have uniformly agreed that the changes are a good thing for their workers, but when it comes to profit margins, they view LL196 as an added cost to doing business in the Big Apple.

“These safety changes have the undesired effect of keeping occasional contractors who do not work full time within the five boroughs out of New York City,” said Louis Monforte, a Westchester County-based electrical contractor and 20-year member of the International Association of Electrical Inspectors.

While opinions may differ on LL196, most professionals in the industry will agree that safety training is always a good thing.

“There is always a need for more safety training within the construction industry, specifically training that is relevant to each and every person who enters a construction site,” White said. “Every day—if not every hour—variables such as means, methods, logistics, tools, etc. can change, which can pose different hazards than originally expected. And therefore, [so does] the need for increased training appropriate to each person’s situation on the construction site.”

Find Us on Socials