Abstract

There has been an increasing emphasis in recent decades to achieve international codes and standards for electrical installations and products. Although the bene-fits of unified documents and products worldwide seem obvious, the migration to such internationalization requires management that considers regional differences of elements such as: the presently installed base, practices used in construction, infrastructure and expectations of users.

The North American electrical safety system has been developed carefully, is operating safely, and is largely homogeneous. Because it is uniform, a single set of product standards for the region is presently realizable. There are elements of this system that should be preserved and perhaps captured in the worldwide system toward which we may be heading. This article examines the hand-in-hand functioning of installation codes and product standards and their enforcement in North America as strengths to be recognized and preserved. These elements and their linkages are a foundation of the safety system to build upon.

Introduction

In the rush toward global harmonization of codes and standards, it is worthwhile or perhaps necessary to understand the cornerstones of safety in the present system. Examining the “life” of an electrical installation, one realizes that a typical installation usually lasts well over 25 years, in many cases. Through its life, the system will be interconnected with similar electrical systems and various types of equipment. Any upgrades and expansions of the system must also be compatible over its life. Although the electrical system may not change rapidly, it must retain safety. This article examines some of the elements of the electrical safety system and recognizes that they are already regionally in place across North America, and suggests that regional harmonization be strengthened on the way toward examining feasibility of worldwide harmonization.

The Homogeneous North American Electrical System

Throughout North America, one finds a 60 Hz system with common voltages and a single, basic practice for grounding of low-voltage, utilization level systems.1, 2 Similar systems are found in many countries in South and Central America and in other regions of the world in which North American style equipment predominates or in which North American companies operate. Contrast this picture with that of Europe in which frequency is 50 Hz and a variety of electrical systems is used, but almost never the American style electrical system. Residence and office distribution voltage is 230 V rather than the 120 V used throughout North America. It should be understood that construction practices, training provided to installation professionals and expectations of users differ from those of North America.

Code Impact

Recognize that the governing installation code largely influences requirements of product standards. Installation codes used in Canada, USA and Mexico are largely similar, and product standards in the region are carefully tied to the codes. By contrast, International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) product standards generally support installation codes employed in European countries and do not necessarily have any relation to those of North America. Electricity production in North America is over 4.5 trillion kWh annually while that of the European Union is less than three trillion kWh.3

The North American Electrical Safety System

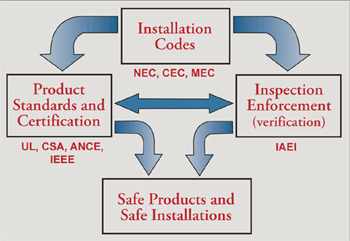

If we step above the physical system to the infrastructure that provides for the safety of installations, we again find common elements throughout NA. Namely, we find linkages among the installation codes, the product standards and the inspection and enforcement system (see figure 1). The linkages provide for safe products and safe installations.

Figure 1

The Installation Codes as Safety Drivers

We have already mentioned that the three installation codes, the National Electrical Code (NEC),4 the Canadian Electrical Code (CEC),5 and the Mexican Electrical Code, NOM-001 (MEC),6 are largely similar. The codes serve as the drivers for safety by directing the safe installation of products and the system. The NEC states in 90.1, “The purpose of this code is the practical safeguarding of persons and property from hazards arising from the use of electricity.” Similarly, the CEC states in Section 0, “Compliance … will ensure an essentially safe installation.” Safety is the focus.

The codes enumerate the requirements for safe systems while helping to ensure the use of safe products. Safe products fit within an integrated system, are rated for their application and meet minimum safety requirements. Code requirements influence requirements of product standards. For example, the product standards establish permitted temperature rises in equipment based on a properly selected conductor being used. The code establishes the selection rules for the conductor on specific applications. Without proper coordination, an improperly selected conductor could lead to equipment operating at temperatures above the permitted limits. This is one of thousands of requirements under which the codes and product standards are linked.

Product Standards Set Minimum Requirements for Safety

In the foreword and introductory sections of North American product standards (e.g., UL Standards) is a statement noting that the requirements in the standard are for safety. When it comes to evaluating product compliance in Mexico, Canada, the USA, or elsewhere the requirements in the standards are safety requirements.

Product standards in general establish minimum safety requirements for performance, construction, marking and certification. Performance and construction requirements do not necessarily relate to the function the product will provide to its user. Rather, these requirements relate to extreme or abnormal conditions products may encounter in service and avoidance of shock or fire hazard under such conditions.

Further, products must be used together in a system. The installation codes provide guidelines, if not requirements, for safe compatibility of products. For example, in temperature testing a piece of equipment, the temperature at wiring terminals cannot exceed the temperature rating of the insulation of the conductors that will connect to them. As another example, current and voltage ratings and operating performance of wiring devices and other equipment used in electrical systems correspond to ratings of overcurrent protective devices. When a 20 A circuit is installed in accordance with the code, all devices certified to linked standards and rated for use in or attached to a 20 A circuit are compatible, from overcurrent protection to wiring to receptacle outlets and beyond. Whether the linkage is pronounced or submerged, there is an important linkage between the installation code and individual product standards.

When products are labeled as having been certified or listed to appropriate standards, additional evaluation by inspection authorities at the installation site is not necessary. Certification to the standard driven by the code means that the product has been determined to satisfy specified safety requirements and can be installed in compliance with the code requirements. Section 90.7 of theNECstates, “For specific items of equipment and materials referred to in this Code, examinations for safety made under standard conditions will provide a basis for approval where the record is made generally available through promulgation by organizations properly equipped and qualified for experimental testing, inspections of the run of goods at factories, and service-value determination through field inspections.” A similar statement appears in 2-024 of the CEC. Recognize that the link between the installation code and product standards exists within the North American electrical safety system and is essential for safe products in safe installations.

Enforcement by Inspection

Throughout NA there are electrical inspectors who are usually an arm of a state, municipal, county or provincial government. The inspector verifies that the installation complies with the code. This is a check on the system by people trained in the code who are removed from the design, construction or operation of the site. In addition, a solid inspection system provides for uniform interpretation of the code throughout the area. Because the inspector must interpret the code relative to a variety of fully-installed systems, he or she helps provide useful feedback to improve the safety and usability of the other parts of the safety system.

Inspection and enforcement ties to the other parts of the infrastructure in that it uses the code as the basis for inspection and provides the legal enforcement mechanism for the requirements. Labeled evidence of compliance with the standard provides the inspector with a means of knowing that products are suitable for application under the code requirements.

Under this system of inspection, products that have not been determined to comply with standards are unlikely to be used. In addition, products that are applied improperly are often identified and not accepted as installed. Of course, methods exist to provide for compliance of special products or products for which no standard exists. This can be accomplished by examination by the inspector if he or she has the proper expertise or examination by a certification organization such as Underwriters Laboratories (UL), Asociacion Nacional de Normalizacion y Certificacion del Sector Electrico (ANCE), Canadian Standards Association (CSA) or other similar organizations.

The International Association of Electrical Inspectors (IAEI) represents many of the inspectors in all three North American countries. One of its objective is: “To cooperate in the formulation of standards for the safe installation and use of electrical materials, devices and appliances and to promote the uniform understanding and application of the National Electrical Code and other electrical codes.” 7

The Three Legs

The North American electrical safety system consists of the three interdependent parts described; codes, standards and inspection. Together they can be thought of as a three-legged stool. Each leg must be present for the system to competently support safety. No leg can adequately stand alone without its tie to the others. It is a proven system built by experience and the hard work of many.

There are a number of apparent forces that may be acting to change or replace this highly effective system. Acknowledging that continuous evolution is desirable and is provided for in the existing system, any great and rapid change could severely challenge the safety of North American electrical installations.

International Electrotechnical Commission

One possible challenge to the system is replacement of existing product standards or even the installation codes with standards of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Under the somewhat misleading assumption that IEC Standards are worldwide standards, such a step would certainly be perceived as a move toward unification of world electrical systems. It would, in theory, allow the interchange of products made to a single set of minimum safety standards throughout the world. This kind of unity sounds good in international trade discussions, but moving blindly would be unwise in regards to electrical safety.

IEC is a standards development organization (SDO) that prepares and publishes standards for electrical, electronic and related technologies. It also operates worldwide schemes for assessing conformity to those standards. Participation is through the national committee of each participating nation.8 Presently there are 63 participating nations. Within its structure there are 172 Technical and Subcommittees and roughly 900 Working Groups, Project Teams and Maintenance Teams. The USA, Canada and Mexico are all participating members.

Since North American countries participate, at least to some degree, in the development of a number of the IEC standards, why should not these IEC standards become the adopted standard in North America? Here are several points to consider.

1. None of the IEC standards are linked to the North American codes. If they are linked to any code, they are linked to the IEC 60364 series of documents. There is no way to tell whether a product that satisfies an IEC standard is compatible for use with other products in a system installed in compliance with a North American code.

2. IEC standards are not generally reflective of regional practices, products and infrastructure employed in North America. One of the greatest influences in the development of IEC standards has been CENELEC.9 CENELEC is a well-organized SDO with membership of 28 participating European countries plus 8 affiliate countries from Central and Eastern Europe. CENELEC standards define the conditions for access of electrotechnical goods and services into the European Market. Of the 63 countries participating in IEC, 33 of them are associated with CENELEC. In the one-country one-vote system of IEC, North America has a maximum of three votes.

3. Though many nations throughout the world contributed to the development of these IEC standards including the USA and Canada, the greatest input to these standards was European. European countries have largely adopted the standards in some form and employ them under their national installation codes.

4. The term international standard does not mean safe for application everywhere.

Four Issues

Four issues have arisen from the standards harmonization and safety perspective.

1. International standard means IEC standard.

2. IEC standards are “better” than North American counterparts.

3. IEC standards can always be adopted or adapted with only minor country deviations.

4. Manufacturers’ reputations and suppliers’ declarations are preferred conformity assessment procedures.

International Standard means IEC standard

Trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the WTO do use the term international standard in their text. The immediate assumption by many is that the term international standard refers to IEC or ISO standards. Although some definitions for international standards may reference IEC and ISO standards as examples, the definitions do not limit the term to standards developed by these organizations.

In comments to the World Trade Organization Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade, the following written comment was made: “The United States continues to believe that bodies which operate with open and transparent procedures which afford an opportunity for consensus among all interested parties will result in standards which are relevant on a global basis and prevent unnecessary barriers to trade.” 10

Internationally accepted standards which provide for this open and non-discriminatory access should be considered international standards. A good example would be the National Electrical Code developed under the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) consensus process.

IEC standards are “”better”” than North American counterparts

IEC and North American standards are all good standards, competently developed and proven by field experience. Components of each system work well when used in the system of infrastructure for which they are intended. One is not better than the other. They are different, based on different practices.

The real issue is the mixing of products designed to standards that are not linked. The differences could result in incompatibilities that affect the safety of the electrical system.

IEC standards can always be adopted or adapted with only minor country deviations.

It has been questioned whether North American standards can be replaced by adopting IEC standards or adapting them via minor in-country “deviations” to account for specific code practices. In some cases, near compatibility exists to start with and adaptation or adoption makes good sense. However, in one case in which “deviations” were listed, the list occupied as many pages as the applicable North American standard. A simple review of the existing installation code does not identify the necessary deviations. Some linked requirements are not obvious, though they are the result of years of co-development of the code and product standard.

Manufacturers’ reputations and suppliers’ declarations are preferred conformity assessment procedures.

Manufacturers’ declarations of conformity to electrical equipment standards are not generally acceptable to users, manufacturers or inspectors in North America. In general, all prefer third party certification for assurance, uniform interpretation and liability purposes. As mentioned above, electrical codes permit installation of equipment that has been approved by the authority having jurisdiction. To grant approval, those authorities typically rely on listing and labeling by an organization equipped and recognized for that purpose. In defining the term listed, the codes in the USA and Mexico specifically discuss periodic inspection of runs of goods at the factory as a follow-up to the initial evaluation and testing program. In Canada, follow-up inspection is also required though not specifically mentioned in the code. Follow-up inspection at the factory is an essential and highly valuable service that provides for conformance through the manufacturing life of a product.

Preserving The System

Several basic and key steps can be taken to preserve and further unify the North American electrical safety system.

1. More clearly cross-reference codes to product standards for safety.

2. Harmonize product standards within North America.

3. Globalize the inspection and enforcement concepts.

There may be useful work in tying product standards to codes. Presently, code requirements are written with no referential or process link to product standards. People who work with codes and standards have informally taken responsibility for updating product standards as codes are revised. Code process participants continually cite the fact that a product standard requires certain tests and construction to justify acceptance of a code rule. Conversely to that it has been stated that if the code does not state a specific product standard, then anything can be used. This thinking can result in detrimental effects to the safety system. To address some of this concern, the NEC was modified to add Annex A that provides an informative list of product standards that are applicable to products that are required to be listed by the Code.

Regarding point 2, there is presently a North American initiative to harmonize product standards for many products throughout the three countries. Harmonization is carried out under the Consejo de Armonizacion de Normalizacion Electrotecnica de las Naciones de America (CANENA) or the Council for Harmonization of Electrotechnical Standardization of the Nations of the Americas. CANENA is an umbrella organization that assembles harmonization committees, composed of members from participating countries, to work together. The standards developed are adopted by the SDO for each country, such as ANCE in Mexico, UL in the USA and CSA in Canada. The result of the process is a single standard published by the participating SDOs and containing the requirements for all participating countries. To a great extent, the standards permit a single product to be applied in any of the participating countries. These standards may also be harmonized with counterpart IEC standards to the extent possible based on infrastructure considerations and the installation codes.

The emergence of harmonized standards throughout North America or throughout the Americas recognizes the similarity of electrical systems and/or of electrical safety systems. It supports the link between product standards, installation codes and the inspection authority throughout the region. It will also provide for a more closely unified view as the next steps in harmonization with or adoption of IEC standards are taken. This is in addition to the benefit of having a single product suitable throughout the region.

On point 3, electrical inspection is a vital public safety function. It helps protect the system from corruption, intentional or unintentional. It provides for uniformity of installations to a recognized safety code. Strengthening of this leg of the electrical safety system should be encouraged worldwide. The International Association of Electrical Inspectors has sections and chapters throughout North America as well as some limited areas in other geographic regions. They provide important activities in training and coordination of the inspection community regarding interpretation of codes and inspection practices.

Opportunities for the Americas

The homogeneity of electrical systems is not solely true for North America. Other nations of the Americas and elsewhere share similar electrical systems and interests for a common safety system. A version of the NEC has been used in Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Saudi Arabia, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. All of these nations would share an interest in product standards that are linked to their national code and could be supportive in making that link by having practices from those codes and standards recognized in either IEC standards or in regional standards.

North American Influence

Customer focus

Customer needs, consistent with safety practices must drive any approach to codes and standards. This statement leads to the thought that systems are best when open to the application of whatever product fits the customer need, a product appropriately certified to whatever standard that properly supports the installation code.

Two systems

It should be recognized that there are two approaches to electrical safety systems in the world today. There is the North American system with its set of practices linked to very similar installation codes. There is also the European safety system with IEC standards at the center. Both are very good, but they are different. Pressuring either one to throw out existing standards in favor of the standards of the other would be unwise, unsafe and impractical.

One system

One worldwide system can only be achieved when standards become truly international. If the international standards are to be IEC standards, they must recognize North American principles and practices. Harmonization means an understanding of differences between installation codes and effective steps to account for them with safe product requirements.

Conclusions

1. The North American electrical safety system is comprised of linked installation codes, product standards and the inspection function. These are the three legs of the system. None of these elements is a standalone element to be replaced without recognizing the other two.

2. The North American system is the largest in the world in terms of electricity consumption. It is largely homogeneous today in terms of the three legs of the electrical safety system and also in terms of the electrical systems installed. This regional unity should be recognized.

3. International standards are not limited to those developed by IEC and ISO. Because of the unique nature of North American electrical systems and the links of the safety elements, unified application of present North American standards is a safe approach that retains the integrity of the infrastructure.

4. Most IEC standards were not developed in consideration of North American installation codes. As such, key linkages for safety between the codes and the IEC standards do not exist and adoption or adaptation of IEC standards must be approached with caution.

5. Identical or equivalent harmonized standards are being developed and published within the three North American countries. These standards contain requirements linked to the codes for safety. They often permit a single product to be used in all three countries, with minor modifications in some cases.

6. The needs of customers, consistent with safety practices, must be a primary consideration in any action.

7. There are presently two approaches to electrical safety systems in the world: the North American system and the European (IEC) system. As we discuss moving toward a single, worldwide system, the infrastructures of both systems as well as of other smaller systems which may have unique needs must be accommodated.

References

1 ANSI/IEEE Std. 142-1991,IEEE Recommended Practice for Grounding of Industrial and Commercial Power Systems.

2 ANSI/IEEE Std. 242,IEEE Recommended Practice for Protection and Coordination of Industrial and Commercial Power Systems.

32005 World Fact Book, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

4 ANSI/NFPA 70-1996,National Electrical Code.

5 CSA Standard C22.1-98, Canadian Electrical Code, Part 1.

6 NOM-001-SEMP-1994, Norma Oficial Mexicana.

7 IAEI.org

8 International Electrotechnical Commission – web site, 2005

9 “CENELEC, Its objectives, structure and activities,” printed 3/6/98 from the CENELEC web site, Brussels.

10 US Contribution to WTO Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade – G/TBT/W/64 – April 2, 1998.

Based on “North American Codes and Standards: A Global Challenge,” by James T. Pauley, P.E., Member, IEEE, Square D Company and George D. Gregory, P.E., Senior Member, IEEE, Square D Company, which appeared as an IEEE White Paper. Copyright, 1998, IEEE.

Find Us on Socials